Solar energy illuminates lives in small Nicaraguan village

By Molly Bilker / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published June 17, 2015

SABANA GRANDE, Nicaragua — As the sky fades from indigo to black, electric lights blink on in Bertha Maria López’s small, gray adobe house off of Highway 15 in rural northern Nicaragua.

In the kitchen under a bare bulb, she flattens masa into tortillas, sliding them into a pan on the wood-burning stove. When her granddaughter gets sick at 11:30 that night, López turns on a light to find medicine and nurse the 2-year-old back to sleep.

Just eight years ago, the López house was dark by sundown. Her son, now a clinical laboratory student at the University of Health Sciences and Renewable Energy in the city of Estelí, studied by the dim light of gas lamps. A middle-of-the-night crisis might have called for flashlights or gas lamps — or nothing at all.

A single solar panel on López’s home today powers four light bulbs at night. And life has changed. She can now play music or charge a cellphone — though not at the same time.

“Month to month, I’m not paying. With the conventional energy, I would have to be saving money to be able to pay,” López said. “That is a great benefit.”

New path

Nicaragua is forging a path as a leader in renewable energy; half the electricity from the country’s energy grid comes from renewable resources. Still, about one-fifth of Nicaragua’s 6.1 million residents don’t live in homes connected to the grid. Like López, they gradually are turning to solar panels to illuminate their lives.

The increasing emphasis on renewable energy in Nicaragua has been a mainstay of President Daniel Ortega’s domestic policy since he and his Sandinista government returned to power in 2007. Nicaragua, Central America’s poorest country, had the region’s highest energy costs. Daily black-outs were the norm in a country highly dependent on foreign oil to fuel its energy grid.

Ortega’s government has invited foreign and domestic investment to help grow and stabilize the country’s power sources through multiple energy alternatives — solar, geothermal, wind and hydroelectric.

Solar’s presence in the country has been growing for years as billboards along the Pan-American Highway in Estelí attest, advertising privately-owned solar companies Tecnosol, Ecami and Nica Solar.

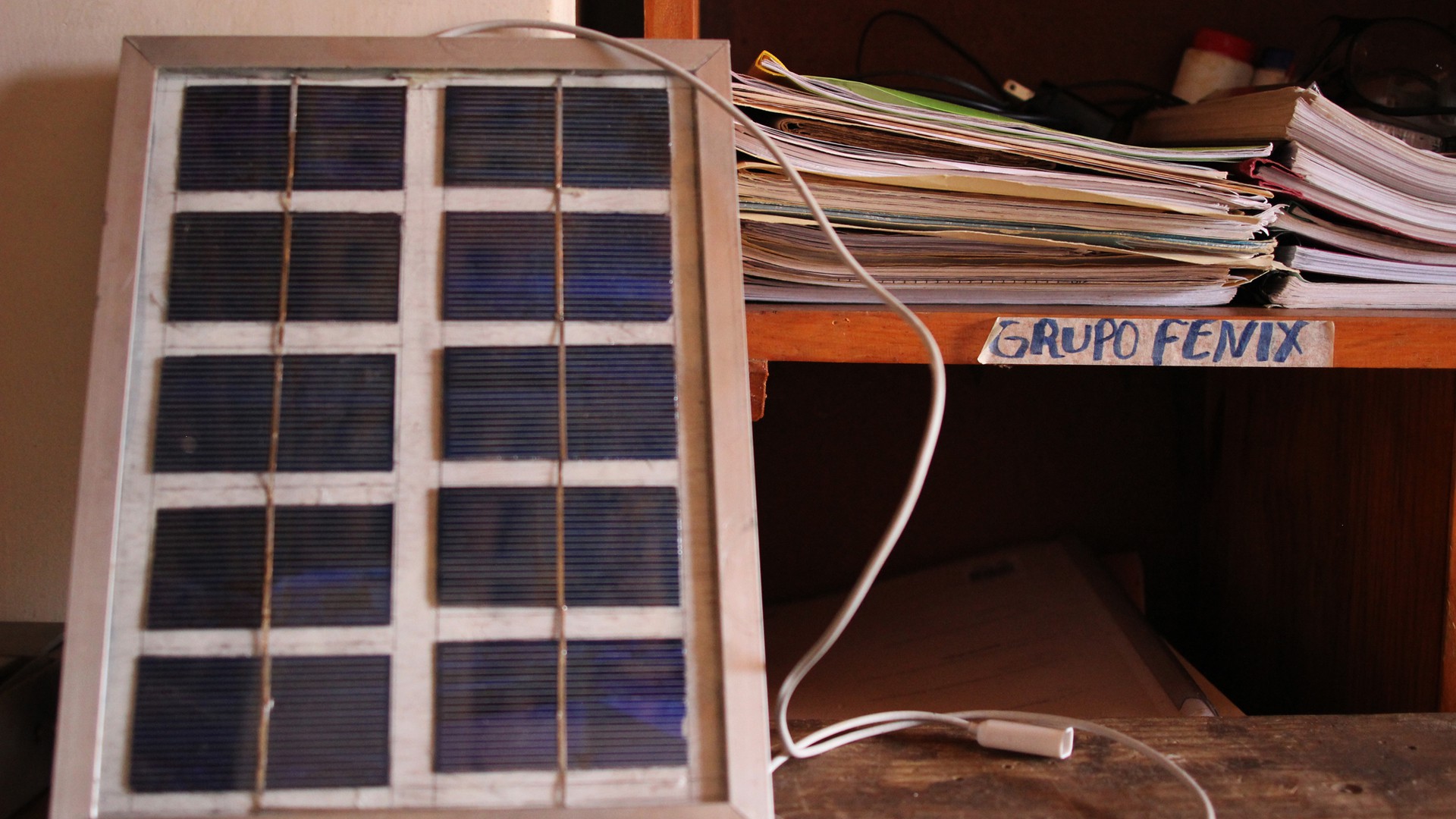

But in Sabana Grande, a community half an hour from the Honduras border, it has been the work of a nonprofit organization, Grupo Fénix, that has made the difference in the lives of people like López.

Grupo Fénix

Started in 1996 with a group of students from Alternative Energy Source Program at the National University of Engineering in Managua, Grupo Fenix has been developing solar projects in Sabana Grande since 1999, said Susan Kinne, who runs the program.

Grupo Fénix got its start when Kinne and the organization’s solar technician, Richard Komp, were offered funding by the Falls Brook Centre in Canada to work with land-mine survivors who were affected by the war, Kinne said. Meanwhile, a group of students from an intensive solar energy course Kinne and Komp were teaching asked for help creating a solar energy fair in northern Nicaragua and invited Kinne to join them.

That’s how Kinne and Komp got involved with the Sabana Grande community, which had members who had lost limbs to land mines and needed sustainable work to support their families.

Today, almost all the homes in Sabana Grande have electricity, said Oscar Omar Sanchez López, internship coordinator for Grupo Fénix. Its success is rooted in a program that invites students from universities throughout the world to stay in the community and learn how to build and install solar panels. The cost of the course pays for a solar panel, which students install on a home at the course’s end.

Most of the solar community lives on one side of the highway, down a dirt path that climbs into the mountainous foothills of Sabana Grande. Dogs lounge near the stout adobe houses along the path as women hang laundry and men go about their daily chores.

The community of Sabana Grande, which consists of 2,019 people in 705 families, was a battle site during Nicaragua’s Contra War in the 1980s. A wide, sturdy tree riddled with bullet holes, the ceiba de oro, or “tree of gold,” sits in the center of Sabana Grande and acts as a point of reference for the community, where the people play sports or hold dances.

Originally, Grupo Fénix worked in 23 communities throughout Madríz, which is one of Nicaragua’s broad regions, known as departments. However, Kinne said the community of Sabana Grande was the most involved and willing to push for change.

“That was all part of the move to, with limited resources, decide not to try to go everywhere and do patchwork work, but to stick with the proactive community with very little external income, earning from our services provided and creating a change in the paradigm of thinking and empowerment that people were actually asking us for,” Kinne said.

In the community, Grupo Fénix does more than install solar panels. Its Solar Center, a small, tranquil plot of land alongside Highway 15, exemplifies a range of renewable energy possibilities.

The back of the Solar Center hosts a solar system that distills water for the batteries used in the solar panels. Two outdoor showers use water heated by the sun in wide, coiled green hoses. Land also is set aside for reforestation, and at the center of the plot sits a squat, brown building, constructed entirely from the area’s natural materials, called El Tesoro del Sol, where the solar youth group meets.

“Mostly government does things at large levels. Those kinds of actions need to be complemented with things that are being done at the low level, at the community level,” Kinne said. “Its impact hasn’t been in numbers of panels put up, but in creating a working example of low-income people who have been marginalized — land-mine victims, indigenous women, young people — having a say in doing innovations that are taken up by others.”

Perhaps the most popular attraction of the Solar Center is La Casita Solar, a restaurant with slick round wooden tables and chairs set under a wide awning. The restaurant uses a variety of methods to prepare food: different types of solar cookers, an improved firewood oven that produces less smoke and keeps kitchen air fresh, and biomass cookers that burn waste from the area’s sugar cane fields.

Behind the restaurant are solar ovens: bright blue, four-legged wooden contraptions with a pane of glass over a compartment for food and a sheet of aluminum foil on the bottom of the lid to reflect light and intensify the heat. A path leads from the solar cookers to the bathrooms, where pipes are routed to an underground biogas stove powered by waste, both human and animal, Komp said.

The solar restaurant is where López works once a week, helping the cooks by cleaning or making juice and salad. A typical meal might consist of rice, beans, potatoes, chicken wings and juice, although cooks also can prepare vegetarian fare. They use the solar cookers to roast coffee beans, which they say better keeps the aroma and flavor in the bean than fire roasting does.

The restaurant is open to the public, but business can be slow. Some days, no customers visit at all. While the restaurant is an example of sustainable cooking and the first of its kind in Latin America, according to Kinne, Lyndsey Chapman, the Grupo Fénix international relations coordinator, said it’s also an example of work in the solar community that may not be tailored to the knowledge of the people living there.

Mujeres

The women who run it, a group known as the Mujeres Solares, have little to no experience starting or maintaining a business, Chapman said.

“The women went with it because it was [Susan’s] dream,” Chapman said. “I know it’s the biggest struggle the cooperative has had … how to make that a sustainable and working business.”

The Mujeres Solares, or Solar Women of Totogalpa, also build solar cookers, host students in their homes, teach others how to build the ovens and plan other projects, such as constructing adobe buildings with natural resources, as in El Tesoro del Sol.

López is the spokesperson for the leadership of the Mujeres Solares. She acts as an adviser to the president, and if the president is absent from a biweekly Monday meeting, López attends instead.

The Mujeres Solares are a central part of the solar community. And what they represent goes beyond their solar work. One aim of Grupo Fénix is what Kinne calls “deep empowerment,” helping the community build its own foundation to better the standard of living from the ground up.

“The Solar Center began from the hands of the women,” said Glenda Mairena, one of the Mujeres Solares. “It was us who built it, and we dreamed of doing all of this, and it has been made into a reality. That has meant that through our work, the other groups have benefited.”

That kind of empowerment is key for the Nicaraguan organization Renovables, which is an association of more than 40 companies and organizations that works to educate communities and create dialogue about renewable energy. The Mujeres Solares are an example of the aims of Renovables, which focuses in part on the relationship between gender and energy, said Renovables Executive Director Lizeth Zúniga.

“If we’re talking about renewable energy, how does the life of the woman change when she doesn’t have to go pick up lumber anymore, when she doesn’t have to be getting on the bus and smelling the fumes?” Zúniga said. “We try to raise awareness for that because women are generators of energy; they are generators of the economy in urban and rural areas.”

Although the Mujeres Solares are examples of gender empowerment, they nonetheless earn a very modest living — López earns $20 to $40 per month — and most cannot afford to buy solar panels. While Grupo Fénix’s courses pay for solar panel materials and installation, the women have a credit system they use to earn their systems, rather than just receiving them.

The women record the hours they work toward empowering the community and spend those hours as credits to buy and maintain a solar power system. The larger community also has a credit system for the same purpose, though it works a little differently. Credits they earn through work are called soles.

There are plenty of ways someone can earn credits, Kinne said, from teaching students who visit to helping with gardening and reforestation or other activities. This process allows community members to help develop the solar work of the community while earning benefits for their work.

“We don’t want to have, ‘you’re getting things because you’re poor,’” Kinne said.

Work like this is known as capacity building — long-term training that helps the community learn to build, install, maintain and use the technology.

Capacity building is key to continuing the production and use of solar panels and other technologies once the organization that brought them has gone. It’s also one of the greatest difficulties Nicaragua faces in bringing solar energy to rural communities, said Elmer Zelaya, executive director at Fundación CHICA, a nongovernmental organization that coordinates a variety of renewable energy projects. Oftentimes, groups will come in, install solar energy projects and leave without properly training people to maintain or repair their systems.

About five percent of homes without electricity from the energy grid have solar power in the area where Zelaya grew up, Cinco Pinos, near the northern border with Honduras, he said. Zelaya estimates that the national proportion of solar power in rural areas is similar — but likely half of those systems don’t work because of technical difficulties, he said.

However, projects that begin through capacity building are becoming more popular in Nicaragua, said Lena Kruckenberg, a postgraduate student at the University of Leeds who has been researching small-scale sustainability projects in Central American countries.

“I think, in particular in Nicaragua, the standard of capacity building is pretty high, and there is a strong interest also because many of these organizations want to see the uptake of the technology to spread across the area,” Kruckenberg said. “If you do a demonstration project and it fails within a year or so, the neighbors are not going to buy the same thing, are they?”

Projects such as Grupo Fénix, despite their high standards of capacity building, also follow a model that may not be feasible for every rural community, Kruckenberg said, as Grupo Fénix's success is grounded in eco-tourism and university visits from other countries.

However, the organization’s work does spread to other rural areas, where members of the solar community go to teach their technologies, Kinne said. Many of the solar technologies, with the exception of solar panels, are made with materials that can be found locally.

Solar in cities

While solar energy has predominantly been a rural issue, Zelaya said, there is a push to bring single-panel projects into cities. Nicaragua offers an energy subsidy for those who use less than 150 kilowatt-hours per month. If energy use goes above that rate, though, costs can triple or quadruple, he said. A solar panel that produces 30 kilowatt-hours per month can make the difference between an $11 to $13 monthly rate and $56 to $60 a month.

Alongside Fundación CHICA in the drive for urban solar energy is Tecnosol, a private company started in 1998. The company is in its second year targeting urban communities, but it has been difficult bringing solar energy into cities, said Tecnosol marketing manager Alfonso Barquero. The company expects it will take three to four years for interest to build.

“This issue is how you approach that market and how you explain to people that it’s worth making an investment,” Barquero said. “They want to have savings, because everyone knows here that we are paying a high cost of electricity — higher than other countries on the continent.”

While solar panels should last 25 years or more, given that they have no mechanical parts to break down, issues can still arise from lead acid batteries not getting enough water, Zelaya said. A new battery costs $150, he said. Gel-based batteries are less likely to fail, but they are rare and cost $400.

That’s where capacity building comes in — if owners can maintain their systems, they’re less likely to break down. A panel must operate for four years to create the amount of energy it takes to build, which means it takes that long for the energy it produces to be considered clean, said Central American University professor Claudio Wheelock. That’s why maintenance is central to successful solar systems.

In the solar community in Sabana Grande, families can pay for battery repairs with their work credits. In López’s home, after she bought her solar panel with credits, the battery malfunctioned and the panel ran out of stored energy quickly. López went to the Solar Center and asked for help, and the problem was fixed within three days.

Athough rural solar projects in Nicaragua face setbacks due to equipment failures, organizations that promote capacity building like Grupo Fénix are making strides. In Sabana Grande, solar energy is playing a key role in renewing life in this village once ravaged by civil war.

“I can’t say ‘I’m going to put in conventional (energy),’ because I don’t have money. It’s very difficult,” López said. “It would be good if, as it is with these people of vision, everyone thought the same way. And were we to have only clean energy, it would be very good.”