Planned for centuries, Nicaragua’s canal plan steps forward

By Cydney McFarland / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published June 17, 2015

MANAGUA, Nicaragua — When the Nicaraguan government passed a law in June 2013 granting a Hong Kong-based company the rights to build a massive canal connecting the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, it divided the country politically.

President Daniel Ortega’s Sandinista government insists the project will pull Nicaragua, the second poorest country in the western hemisphere, out of poverty.

“I believe if the canal is ever built, it will be better for not just Nicaragua but for the whole region,” said Benjamin Lanzas, a member of the Canal Advisory Committee. “In 10 years I see Nicaragua coming out of poverty; I see Nicaragua not being the poorest country in Central America but the richest country in Central America.”

The canal’s opponents claim it is a looming environmental disaster for which planning is shrouded in secrecy and that could displace thousands of people. Some opposition leaders doubt that this project will ever come to fruition.

“When they started with the law, they said there will be something like a million new jobs by this year and an increase in the pay, something like 15 percent,” said Congressman Luis Callejas, a liberal from the opposition Nicaraguan Democratic Bloc who has been vocal about his dislike for the law and the lack of transparency surrounding the canal project. “Nothing like that has happened.”

Visibly, little has happened since a December 2014 ceremonial groundbreaking that took place in the capital city of Managua, over 70 miles from the proposed canal site. Since then the only construction has been the repaving of roughly six miles of road near the city of Rivas, where the canal will meet the western shore of Lake Nicaragua, known locally as Lake Cocibolca, the key link in the Pacific-to-Atlantic passageway.

The proposed canal would be one of the great engineering feats of all time. It is almost three times longer and two times deeper and wider than the Panama Canal, which is undergoing a $5.2 billion expansion. There are also plans to build hotels, an airport and a golf course along the canal route.

The project is conservatively estimated to cost between US$40 billion to US$50 billion but there’s been very little information as to how the Hong Kong-based company HKND, which has never built anything even close to this scale, is planning to fund the project.

There also has been no published study on the potential environmental impact the canal could have or what the impact could be on the people who live in the Canal Zone or who rely on the lake’s water. Supporters of the canal insist that these issues are being addressed.

“Daily, constantly, the national, even international, modes of communication have been informing step by step about the construction of the canal,” said Ulíses Antonio Chávez, a supporter of the Nicaragua Canal and part of a Sandinista youth movement in Granada. “The results that they’re producing, the studies that are being done in relation to its feasibility, the environmental impact. That’s one of the topics that the government hasn’t disregarded at all, actually the most important aspect that’s being assessed within the construction of the canal.”

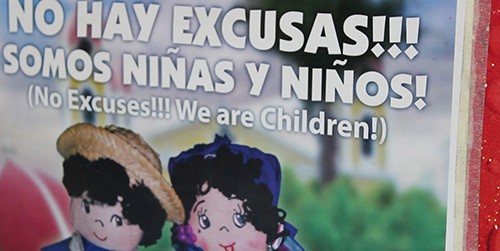

Protestors have focused on these concerns and also have spoken out against Law 840, which they say gives the HKND control over the Canal Zone without sufficient oversight.

“We lost our right to any part of the country; this company HKND, they have the right to build anything and to get anything in the country. They have the right to expropriate land from anybody anywhere in Nicaragua,” said Ana Margarita Vijil, the president of the MRS, a political party banned in 2008 from running in elections.

Law 840

Vijil contends that Law 840 essentially gives up the sovereignty of Nicaragua to Chinese billionaire Wang Jing’s company HKND, which has no obligation to complete the project as planned, doesn’t hold it to any environmental standards and gives no plans on how to deal with the displacement of people in and around the Canal Zone.

“It’s going to be a huge immigration, you know, you lost your community, your way of life and the law, the concession doesn’t offer another place where you go,” said Vijil.

The law was passed in about three days, with no public debate, according to opposition congressmen Callejas and Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, the son of Violeta Barrios Torres de Chamorro, who was the president of Nicaragua for six years after defeating current president Ortega in the 1990 election.

“There have been hundreds of laws that have been approved with much more consultation, in the proper way. It was approved like it was in a hurry,” said Chamorro. “We opposed it strongly and, of course, we voted against, but that was all, they had the votes.”

Since the law was passed, 32 different appeals have been filed against the law. President Ortega has been accused of treason by opposition leaders like Vijil, while leaders from the indigenous communities in the east of the country have brought their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington, D.C.

“We know that there are groups that aren’t in favor.” said Chávez. “They don’t see the project as a national project and a global project, but rather they’re seeing it as a party project. They believe that this is a project of the party. Yes, it’s true who leads the government, Commander Daniel, the Sandinista National Liberation Front, but they’re not thinking of just benefitting those who are Sandinistas.”

Despite some vocal opposition to the canal, polling has shown that the general public views both the canal and Daniel Ortega positively. In a poll conducted by M&R Consultants in January 2014, Ortega had a 65 percent approval rating overall and 82 percent approval within his own party, according to a the Nicaraguan Dispatch newspaper. Opposition leaders say that this stems from a lack of knowledge about what is really going on.

“Ortega is a very talented person; he’s not dumb. He has good publicity; practically, they control about 95 percent of the TVs in Nicaragua and 95 percent of the radios in Nicaragua,” said Callejas. “We have been dreaming about a canal for the past 200 years. So it’s good promotion to say ‘We’re going to have a canal and everybody is going to get rich.’”

History

This is not the first time plans have been made to build a canal through Nicaragua. Historical maps show the conquistadors investigated the idea in the 1500s but nothing came of it. The idea popped up again during the American Gold Rush when Cornelius Vanderbilt used the San Juan River and Lake Cocibolca to transport people from the eastern United States to California.

That proposed canal was put on hold when William Walker, an American, invaded Nicaragua with a private army, declared himself president and ruled for almost 10 months. Nicaragua was also the proposed site for a U.S. canal in the 1800s, but the plans were moved to Panama in 1904, and the U.S. completed the Panama Canal in 1914.

Panama Canal

The proposed Nicaragua Canal faces competition from an expanded Panama Canal, which has been undergoing renovation since 2007. The project involves adding new locks and dredging the canal, making it deeper and wider to accommodate larger ships. The project is expected to be completed in late 2016.

According to a statement issued by the Panama Canal Authority, “the Panama Canal Expansion Program allows Panama to take advantage of opportunities across multiple sectors, unifying the country as a hub of transportation, logistics and services, for the benefit and development of the global maritime sector.”

In the same statement, the Canal Authority responded to the proposed Nicaragua Canal, saying, “As we look to the future, the Canal is well positioned for decades to come to continue to capitalize on its privileged geographic location through strategic planning, exemplary customer service, dedicated employees, world-class management and continual investment. Competition comes and goes; we have always had it and always will.”

In its project description, HKND wrote that the Nicaragua Canal is targeting those increasingly large vessels that can’t fit through the Panama Canal, even with the expansion. HKND also pointed out that the Panama Canal has affected the dimensions of modern ships and predicted that the Nicaragua Canal could do the same, inspiring the construction of even bigger cargo ships in the future.

“You have to remember that the Grand Canal is going to unite. It’s going to unite, and it’s going to reduce costs for the whole world, and apart from this, it’s going to be a better canal than the one in Panama,” said Chávez. “That’s the reason Panama, currently, is improving its canal because they’re viewing Nicaragua as competition, because, realistically, once Nicaragua has constructed the canal, it’s going to be more feasible for a lot of businesses, big businesses, to come to Nicaragua to use the Nicaraguan canal, than to use the Panama Canal.”

Wang Jing has a net worth of about US$7 billion and is the 195th richest person in the world, according to Forbes, but primarily private investors will fund the US$50 billion project. In June 2013, in an interview with Bloomberg, Jing said that he had successfully recruited investors for the canal project. However, the names of these investors have yet to be released.

The Grand Canal

If constructed, the Nicaragua Canal will be one of the biggest civil engineering projects of all time. In the roughly 170 miles of canal route, about 4,000 cubic meters of dry land will need to be excavated and roughly 980 cubic meters will need to be dredged. The majority of the dredging will be in Lake Cocibolca, which has an average depth of about 42 feet, less than half of the depth needed for the canal.

“As you get to the east coast of the lake, the water gets about up to your knees or less. I have been there and even a kayak hits the rocks,” said Congressman Callejas. “They have to dig in there and dig hard.”

Seventy miles of the roughly 173-mile canal route cuts through Lake Cocibolca, and the majority of it will require substantial dredging of the lake bed, which is made up of sand, gravel and chunks of volcanic rock, according to Congressman Chamorro. He said HKND plans to use dynamite and controlled explosions to blast these rocks out of the canal’s path.

“They actually had thought about it, and they gave an incredible amount of dynamite,” said Chamorro. “So much that they said that is another business opportunity for Nicaragua, a dynamite factory; I couldn’t believe it.”

The roughly 5,000 cubic meters of material will be moved into three disposal sights that will be placed in and around Lake Cocibolca. These disposal sights will be built up into islands on the eastern side of the lake, according to HKND’s canal project description.

The canal project will also incorporate a stand-alone dam, breakwater walls at the Pacific, lake and Caribbean entrances and ports at the Pacific and Caribbean entrances. HKND also plans to build two cement plants for the canal construction and power generating and transmission facilities to run the canal. In addition, a bridge will connect the Pan-American highway on the west coast and a ferry will run across the canal in the eastern part of the country. Other proposed projects, such as a trade zone, hotels and airport were not included as part of the original project plan.

“Construction of these facilities would begin when the canal construction is advanced, which is five or more years in the future,” HKND said in a project proposal published on its website. “Further, little information exists at this time to allow a full impact assessment of these facilities. For these reasons, these other facilities are not included as part of the proposed project.”

Future of the Canal

Despite a very vocal opposition, 70 percent of Nicaraguans believe the canal project will bring jobs and investments to the country, according to a poll by the Sandinista Consultora Siglo Nuevo, published in the Nicaraguan Dispatch.

Chávez said the government has promised the project will create more than a half million skilled jobs.

Nicaragua is the second poorest country in Central America, with a GDP of roughly US$11 billion. The unemployment rate was just over 7 percent in 2013, and 40 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

“What we’re talking about is that we would arrive at an increase of even five times more growth,” said Chávez. “That is to say, the construction of this canal is going to be one of the fundamental pillars for the reduction of poverty in Nicaragua.”

Opposition leaders don’t deny that a canal could be beneficial for Nicaragua but say that the social and environmental risks are too great. Aside from the outrage over the Law 840, opposition leaders are concerned about the possible social consequences of a canal. Thousands of families who live in and around the over 2,000 square miles of Canal Zone will be displaced, and neither the Nicaraguan government nor HKND have released plans on where these people will go.

“In Spanish it is called desarraigo,” said Chamorro. “Desarraigo is when you are removed from your land and your way of living and every possession that you have.”

With only one bridge and one ferry crossing planned, the canal will essentially split the country into two parts. The canal also cuts across the lands of the indigenous Rama on the east coast, splitting an already endangered culture in half.

Then there are the environmental issues. Lake Nicaragua is home to sawfish and freshwater sharks, sea turtles hatch on the Pacific beaches and rain forests are home to a wide variety of plants and animals. The lake is also the largest freshwater reservoir in Central America.

Despite all this, supporters of the canal seem confident in the success of the project.

“The truth is that, in fact, the project is already being produced. The plans are already made, the licensee that is going to construct the Nicaraguan canal is here, and the monetary support is here,” said Chávez. “More than anything, as I said, it’s not only a national project being seen here. Yes, true, it’s Nicaraguan, but not only Nicaragua is going to benefit, but rather the whole world will benefit.”