Nicaragua’s interoceanic canal prompts worries about human trafficking

By Elizabeth Riecken / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published June 17, 2015

MANAGUA, Nicaragua — Human rights workers are worried that the land ceded to a Chinese development company as part of a proposal to build a 173-mile canal across Nicaragua could become lawless territory and ruin progress made in combating human trafficking.

“Nicaragua is a transit country, where victims are only brought and taken, and it is not the country of destination,” said Adrian Uriarte, a journalism counselor for Universidad de Ciencias Commerciales in Managua, who heads an initiative to train working journalists covering human trafficking issues. “In the case of the canal, the possibility is there … The canal comes to undo everything we have done.”

Three years ago, Nicaragua became the only “Tier 1” designated country in Central America, the highest positive ranking by the U.S. Department of State recognizing efforts to eliminate human trafficking. This designation, however, does not mean that the country no longer has problems with human trafficking.

Nicaragua’s human trafficking history involves both sex trafficking and forced labor. Victims are typically moved from rural towns to larger cities, such as the capital of Managua and the tourist center of Granada. Nicaraguan trafficking victims also have been found in other countries in Latin America and even the United States.

Nicaragua has made steady progress in combating trafficking by stepping up prosecutions and education campaigns. But, according to the State Department’s 2014 Trafficking in Persons report, Nicaragua continues to suffer from “a lack of comprehensive data on human trafficking.” This makes it difficult to verify the help victims received after being identified.

Still, Nicaragua progressed enough to move its rating up a notch in 2012. Some worry that progress could be threatened by the building of the canal which would require an estimated 50,000 construction workers, half of whom would come from outside of the country.

Law 840, which authorizes the Hong Kong Nicaragua Development Investment Company to build the canal, leaves unclear who is in charge of enforcing laws in the Canal Zone, according to Azahalea Solis of the Autonomous Women’s Movement, a group promoting women’s rights.

“The state made its jurisdiction disappear in the concession (of the canal’s land), and so there will be no laws there,” said Solis.

“The canal and Nicaragua’s growing tourism industry are good opportunities for the poverty stricken country but also could hurt some of the progress that has been made," said Phillippe Barragne-Bigot, a UNICEF worker who has been stationed in Nicaragua for the past three years.

“The country has new opportunities, and these new opportunities could become sources of problems. The tourist sector grows annually with 10 percent growth; then you have the construction of the canal. These are huge opportunities for the country, but at the same time, they could become the source of problems,” said Barragne-Bigot..

Effectiveness of new trafficking law

In January 2015, Nicaragua passed a law that would criminalize all aspects of trafficking, including illicit adoptions, forced marriages and organ trafficking. It also would establish a comprehensive database for human trafficking-related crimes, according to a report in El Nuevo Diario.

While viewed as a positive step, Solis said it is unclear how aggressively Nicaragua plans to implement the law. “There is a problem of regressing, and there is a serious problem with the lack of dialogue. And in a country where dialogue is broken — and in Nicaragua it is broken — it makes it difficult for women’s rights and trafficking.”

Barragne-Bigot said information is key in the battle against human trafficking and making sure the public is aware of warning signs.

“If people are informed they are less prone to being exploited. Sometimes it starts with labor exploitation; it is very insidious,” said Barragne-Bigot. “Compared to other countries, it is under control, but it could become a bigger problem.”

According to opposition newspaper La Prensa, President Daniel Ortega had not had a press conference in more than 3,000 days in early March. He communicates primarily through daily 30-minute news programs anchored by the first lady Rosario Murillo that air on government-controlled television.

“From only one source; there is no dialogue,” Solis said. “They only call a few journalists who are a part of the system. They have no right to ask questions, or they give questions before asking … not only on the subject of human trafficking.”.

One of the main obstacles to stopping human trafficking in Nicaragua is how victims are viewed.

“The cultural part — even if a girl is underage, if she has sex, she becomes a woman,” said Uriarte. “She becomes vulnerable because they don’t see her as a child. If she has been a mother or has had sex, it is easier to trick them.”

Non-governmental agencies such as UNICEF have tried to step into the void for victims. UNICEF’s current mission in Nicaragua is to focus on supporting already established government programs to promote a “culture of peace,” which includes helping child victims of human trafficking and other abuses. But midway through a five-year program that began in 2013, UNICEF has been unable to generate enough donor interest to fully support its goals.

Human trafficking prevention is especially important in tourism towns like Granada, a revived colonial city on Lake Nicaragua. Areas such as these are more vulnerable to human rights violations because of the large number of people who visit. According to the U.S. Department of State, Nicaragua has become a destination for child sex tourists from the United States, Canada and western European countries in recent years.

It is a problem openly acknowledged by the Nicaraguan government. Prominent government signs are visible in restaurants in Granada, proclaiming that Nicaragua is against the abuse of children.

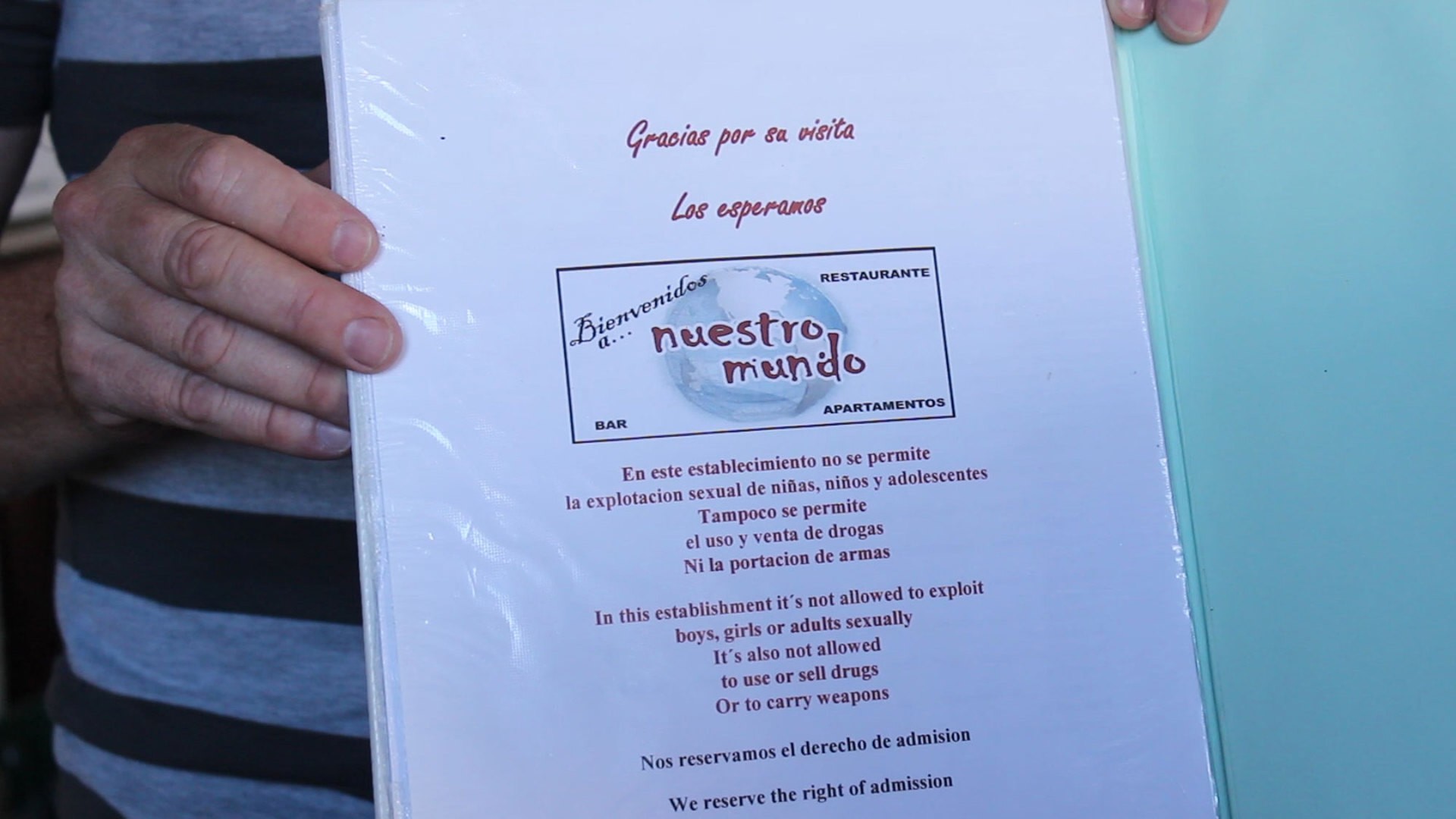

In some restaurants, such as Nuestro Mundo, owners have taken it upon themselves to put warnings on their menus, saying solicitation of any kind will not be tolerated on their properties.

“The ministry of tourism talks to us businesses about preventing human trafficking,” says Gerrit Rosbeek, who owns Nuestro Mundo and the apartments above the restaurant. “I think it’s absolutely part of our responsibility to watch and make sure there is no exploitation of children."

The canal project has raised concerns that a large foreign construction workforce will undo progress made in the country.

“The main buyer of those who have been trafficked are people who are in transit,” said Uriarte, the university journalist. “That’s especially a problem when (the victims) are young.”

UNICEF’s Barragne-Bigot is more optimistic progress will continue to be made. “It is better to prevent than cure and I think Nicaragua very courageously decided to prevent and to foresee any potential problems before those problems become out of hand,” he said.

Solis is less sure of what the massive project may mean for Nicaragua.

“I’m a little pessimistic because it’s a problem of a lack of institutionalization,” Solis said. “There are no limits. There are levels of corruption… it’s important to have laws that the authorities respect. Society will soon know what is happening. Meanwhile, it looks like Nicaragua has no problems.”