Love him or hate him, few doubt Ortega’s political skill

By Charles McConnell / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published June 17, 2015

MANAGUA, Nicaragua – To some here, President Daniel Ortega remains the revolutionary liberator who helped wrest control of Nicaragua in 1979 from the 43-year, U.S.- backed reign of the Somoza family.

"Just as they fought to liberate the people, we as youth are now carrying this legacy forward in a different way," said Ulíses Antonio Chávez, a member of the Sandinista youth movement in Granada.

To others, though, Ortega has become the same type of ruler he helped depose.

"We like dictators. We spent 40 years with Somoza, and we don’t know how many years we’re going to spend with this guy," said Congressman Luis Callejas of the opposition Alliance Caucus Independent Liberal Party.

Whether supporter or detractor, Ortega’s comeback and consolidation of power are testaments to his political skill.

"[Ortega] is a very brilliant politician," said Charles Ripley, an Arizona State University professor who has spent much of his career studying Latin America and lived in Nicaragua for eight years. "He has played his hand that wasn’t very good after he lost the [1990] election so well to come back to power… He’s actually a brilliant strategist within the Nicaraguan context."

Nicaragua Now

Ortega, 69, remains widely popular in his unprecedented third term as president. A public opinion poll released by M&R Consultants in January 2014 showed him with a 65 percent approval rating, according to The Nicaragua Dispatch.

Driving between Granada and Managua, massive billboards and posters of Ortega line the highway. Members of Ortega’s Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, or Sandinista National Liberation Front, stand by giant yellow sculptures in matching attire. The occasional FSLN rally, complete with flags and signs, touts the socialist-leaning agenda.

But while outwardly Nicaragua seems like a place of unity, there is mounting opposition centered around the proposed construction of an inter-oceanic canal and Ortega’s bold moves to hang on to power indefinitely.

By controlling the flow of information and manipulating both national and municipal election results, Ortega has become a dictator, contends Ana Margarita Vijil, president of the Movimiento de Renovación Sandinista, or Sandinista Renovation Movement.

The MRS doesn’t currently have legal status in Nicaragua, a fact Vijil attributes to the party being anti-Ortega.

"My party, we are against so [Ortega] cancelled our…status. So we cannot run in elections because we are not legal," Vijil said.

Vijil complains that Ortega has rigged the electoral system heavily in his favor. After winning his first election for president in 1984, Ortega was defeated in 1990, 1996 and 2001 before being re-elected in 2006. In 2012, the country’s Supreme Court, made up largely of Sandinista supporters, overturned a law banning a Nicaraguan president from holding consecutive terms, leading to Ortega’s re-election. And in 2014, Nicaraguan lawmakers eliminated presidential term limits altogether, with opponents saying Ortega can be re-elected for life. He reportedly has indicated interest in seeking a new five-year term in 2016.

In addition, Vijil contends there are voter irregularities – dead people voting, denial of voting rights to opponents of the government and a lack of election oversight — that need to be addressed in order for Ortega to be voted out of office.

"It’s a huge challenge for us, but I think it’s possible that if we work together, everybody, with these kind of things like the canal and other stuff in Nicaragua—people are not happy," Vijil said about next year’s elections.

Approval of the proposed 173-mile canal, which would connect the Pacific and Atlantic oceans in an engineering marvel that would pass through Lake Nicaragua, has already created backlash, particularly from those who would be displaced from their homes. There have been more than 40 protests across the country and opposition in the southern region of Nicaragua through which the canal would pass is mounting.

"For something so important, so fundamental … it was really moved into a rush," said Congressman Pedro Joaquin Chamorro Barrios, son of Violeta Chamorro, the first female president of Nicaragua who defeated Ortega in 1990. "There have been thousands of laws or hundreds of laws that have been approved with much more consultation … the proper way. It was approved like it was in a hurry; in three days, a law that gives away sovereignty of Nicaragua was passed."

Sandinista supporters point to the Ortega government’s successes as reason for his continued support.

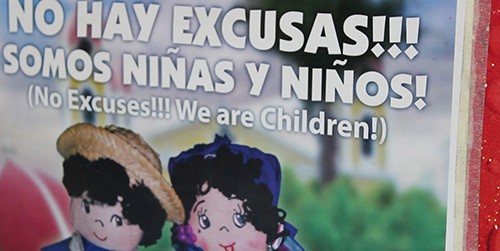

Under Ortega, Nicaragua has made progress towards many of the United Nations’ eight Millennium Development Goals, according to the United Nations profile on Nicaragua. The goals are to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; achieve universal primary education; promote gender equality and empower women; reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases; ensure environmental sustainability; and develop a global partnership for development.

According to World Bank data from 2010 to 2014, Nicaragua spends a higher percentage of its gross domestic product – the total of goods and services produced in the country - on education than all other Central American countries except Costa Rica. Under Ortega, Nicaragua has increased its spending on education to 4.4 percent of the Gross Domestic Product, up from 3 percent in 2000.

And Chavez, the young Sandinista, said that has resulted in more access to education.

"Before, if you wanted to study a technical career, you had to pay a fee that was similar to that of a college career. Today, a technical career is free of charge, just like an elementary school or a high school," Chávez said.

While the average Nicaraguan remains desperately poor, earning about $95 a month at minimum wage, Ortega’s supporters contend progress is gradually being made in wage levels as well.

"During the past seven years, agricultural workers’ income and wages grew, showing the effectiveness of programs for the rural sector which is where there are higher rates of poverty and malnutrition, and taking away the economic reason for migration," concludes a June 2014 report by the Nicaragua Network, a project of the Alliance for Global Justice, a Tucson-based organizing network that supports leftist causes globally.

"The two countries that have reduced inequality most in Latin America are … first Venezuela, second Nicaragua," said Katherine Hoyt, director of the Nicaragua Network. She spent 16 years living in Nicaragua and working for the Sandinistas.

According to Hoyt, people like Ortega and the late Venezuela leader Hugo Chavez have been able to make "necessary changes in their countries that have benefitted the poor majority."

Nicaragua also has made huge jumps in promoting gender equality and empowering women. Ortega has given his wife, Rosario Murillo, a prominent role speaking through national broadcasts about national issues, although critics point out that Murillo and Ortega limit access to journalists while controlling much of the media. Additionally, since Ortega took office in 2007, the proportion of seats held by women in the national parliament has more than doubled, from about 18.5 percent in 2007 to 39.1 percent, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean of the United Nations.

Of 13 specific target objectives that measure the progress towards the eight U.N. goals for 2015, Nicaragua has achieved over 90 percent compliance on nine, according to the economic commission.

Nicaragua lags farthest behind in access to new technologies, which helps explain the low Internet penetration. According to Internet World Stats, only 15.5 percent of the population uses the Internet in Nicaragua, the lowest among all Central American countries and Mexico.

But a key statistic in Nicaragua’s favor is that it is the safest country in Central America despite being the poorest. While Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala have been besieged by gang violence, even critics grudgingly acknowledge that the Ortega government has nipped it in the bud.

"I give [credit] to the police," Callejas said. Callejas said that while the police have become "more Ortega’s police," the professionalization of the force began in the 1990s. The police have done a good job integrating within communities, Callejas said, citing a case in which gang member from El Salvador tried to hide in Chichigalpa but lasted only two days before being caught and deported.

Eric Olson, the associate director of the Latin American Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., said "the relationship between community and police is stronger in Nicaragua than in any of the other three countries," referring to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. He credits both Violeta Chamorro and Daniel Ortega.

The United States

Nicaragua also has cooperated with U.S. efforts to combat drug trafficking, according to Olson.

"The one area where there seems to be pretty good collaboration is on counter-narcotics between security forces in Nicaragua and South Com," said Olson, referring to the United States Southern Command, a branch of the Department of Defense that deals specifically with the Caribbean, Central America and South America.

Callejas takes the collaboration with a grain of salt, however.

"The United States has interests, not friends," Callejas said. "While they believe in democracy, they don’t support democracy always. What they want right now is something to withhold drugs and migration to the United States."

Over the past several hundred years, the United States’ history with Nicaragua has been complex and dominated by those "interests."

A Brief History

Nicaragua’s entanglements with the United States date back centuries.

In 1856, an American named William Walker declared himself president of Nicaragua, legalized slavery and made English the official language, according to "Nicaragua: Living in the Shadow of the Eagle." His reign lasted less than a year.

Intervention by the United States would be a theme over the next 140 years. Beginning in 1912, the U.S. Marines would occupy Nicaragua for 21 years with the exception of nine months in 1925, when U.S. troops withdrew until a civil war erupted, prompting their return.

1936 saw the beginning of the American-backed, 43-year dictatorship of the Somoza family. This period saw varying levels of ruthlessness by the Somozas and their National Guard. Eventually, the National Guard had its hand in all aspects of Nicaraguan politics and society, with a key goal of suppressing opposition movements.

The Somoza family was overthrown in 1979 after a civil war led by the Sandinistas. Daniel Ortega played a major role, as he and his brother were among the nine leaders of the reunified FSLN party that led the revolt.

The 1979 Sandinistas were socialists — which some argue differs from their ideology today — and resented the United States for its support of the Somoza dictatorship. When they took control of the country, the USSR took notice, leading to Nicaragua being one of the many proxy sites for the global chess match between the United States and the Soviets.

President Ronald Reagan even went so far as to fund the Contras, a group that took to arms and resisted the new Sandinista government throughout the 1980s until a ceasefire in 1988, further complicating U.S.-Nicaragua relations.

U.S./Nicaragua Relations Today

Today, there is much less direct U.S. involvement in Nicaragua than there has been in years past.

"[Nicaragua] was one of the front line countries of the Cold War in the 1980s," Olson said. "With the end of the Cold War, with the fact that there have been other crises in Central America that have affected the U.S. more directly, and the fact that Nicaragua itself has found some stability, at some considerable price to democracy, but nevertheless some stability … [ Nicaragua] is not the priority it was obviously during the end of the 70s, throughout the 80s, into the 90s even."

Olson and others argue that the United States should be keeping an eye on Nicaragua, however, especially if the canal project moves ahead.

Anthony Quainton, former U.S. ambassador to Nicaragua during the Reagan administration from 1982 to 1984, says massive Chinese investment in the developing world needs to be monitored and analyzed.

"And this (canal proposal) is just another example … of their (Chinese) outreach into parts of the world where previously they had relatively little political or economic influence," said Quainton, "so that is obviously a potential concern to the United States."

Olson said the "stakes become much higher for the United States," if there is proof that the Chinese are really going through with the canal, although he doesn’t think it would warrant any action to stop the construction.

The United States is working toward stabilizing relations with the Ortega government. The U.S. Agency for International Development operates in Nicaragua, focusing on four main goals, according to its website: HIV protection and awareness; education; public-private partnerships; and promotion of "democracy by training young, emerging democratic leaders and providing technical assistance to bolster civil society engagement and improve local governance."

Olson acknowledged the irony between USAID's mission and the fact that "stability in Nicaragua has come at the expense of more robust democracy."

Despite the cooperation, Nicaragua is still largely viewed by U.S. officials in much the same way as other socialist-leaning Latin American countries. In March, Roberta Jacobson, assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, requested a 34.7 percent increase in funding to address human rights issues in those countries.

"The request maintains important support for freedom of the press, human rights and democracy in the hemisphere, including in Cuba, Venezuela, Ecuador and Nicaragua. The United States has a long history of supporting human rights and civil society. Our request continues this approach," said Jacobson, according to a transcript of her testimony before the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere.

Still, unless the situation changes, Olson believes Nicaragua will remain "on the backburner" as far as American foreign policy is concerned.

And as Ortega prepares to run for an unprecedented fourth term, even supporters like Hoyt who extol the successes of his tenure wonder how long his reign will and should last.

"It seems to be a sad characteristic of the folks who are seriously committed to changing their societies in ways that benefit the poor," Hoyt said. "They also seem to think that they are sort of the inevitable and perennial presidents, and that they should be elected eternally."