Foreigners seek new lives in Nicaragua

By Mykaela Aguilar / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published June 17, 2015

GRANADA, Nicaragua – Jim and Carol Lynch love the simplicity of life in Nicaragua.

They have a maid, a gardener and nearly free medical care. The self-described “liberal humanitarians” say they can smoke marijuana freely. They live comfortably in the colonial city of Granada on Social Security benefits. And Jim hasn’t had to learn a word of Spanish.

The Lynches, who moved to Costa Rica from Tennessee after retirement in 2008, moved to Nicaragua two years later after realizing it wasn’t dangerous and it was cheaper than life in the States.

They are part of a small but growing number of American and Canadian immigrants – often called expats – moving into two of Nicaragua’s primary tourist towns. Granada and San Juan del Sur are home to foreigners from all over the world who come to live relatively easier lives with a lower cost of living.

Some are setting up businesses such as restaurants, travel agencies and English schools. Real estate companies like Re/Max and Century 21 have set up offices to cater to foreign buyers.

The U.S. consulate office in Managua didn’t have any estimates of how many Americans are living full time in Nicaragua. But many come on short-term, 90-day tourist visas, exit the country and almost immediately return, getting a new visa and three more months of temporary, legal residency.

For those living in San Juan del Sur the process can take as little as three hours to travel to Costa Rica, cross the border and then re-enter Nicaragua for $25 in fees.

When the Lynches initially moved to Costa Rica, it was for the cheap medical care. They had retired and had a three-year gap before they would be eligible for Medicare in the States.

The transition to Central America has gone so well that Jim hasn’t been back since he and his wife left in 2008 and Carol has visited just once. They have no plans to return permanently.

‘We can’t go back to the states because we couldn’t have a maid,’ said Carol. The couple spends a total of $750 per month, with rent, aesthetician and gardener included.

Nicaragua has made Elisha and Gordon MacKay’s five-year plan – to retire and live on the beach by age 40 – come true early.

The MacKays, in their 30s with no children, are immigrants from Canada who got married in Costa Rica and settled in San Juan del Sur, a beach town off the Pacific Coast, known for surfing. They came to Nicaragua, they said, with four suitcases and a carry-on.

They now live off their investments and concierge work they do on the side. The MacKay’s spend $1,500 a month, which includes frequent eating out, social activities and motorcycle trips.

“There are ways we could generate income, but we’d have to sacrifice time, and I like having free time,” Elisha MacKay said.

Andrea Pellegrino and her husband, Julio Carta, are raising their two daughters in Granada where they run a bakery, Pan de Vida. The front of the building is where they bake and sell their products, and they live in the back in order to consolidate their $800 rent on Calle Calzada, a popular tourist spot in town.

Their daughters, aged four and nine, attend a private international school at a cost of $200 each month, where they have become fluent in Spanish. The parents are happy with the quality of their daughters' education.

Pellegrino and her daughters are Canadian citizens while Carta is from Venezuela, but when they talk about being immersed in the culture, Pellegrino said, “We’re Nicaraguan.”

Making the Move

The foreigners who do obtain permanent residency must go through an application process that includes meeting a series of standards such as showing financial solvency, proof of good health and proof of no criminal past.

Patricia Sanchez used to work in the government immigration agency in Nicaragua and now makes a living helping expats obtain permanent residency. She says the process is tedious, but with the right paperwork, applicants are almost always accepted, unless they have an outstanding criminal record.

Nicaragua does not have a formal extradition treaty with the United States, but it has cooperated in the past. In 2013, Nicaraguan authorities handed over Eric Toth who was on the America’s Most Wanted list on suspicion of producing child pornography. Toth was living in Esteli under an alias when local officials arrested him.

It is no secret that among the expat community, there is a segment of the population that has moved to Nicaragua to avoid arrest in their home countries. Foreigners and locals freely discuss the feelings they have towards those in trouble with the law.

Frank Ingram, an immigrant from Florida who lives in San Jorge, said he tries to stay away from most other expats, calling them trouble.

"At least 50 percent of them are escaping something. They’re liars. They come here to start a new life," Ingram said.

Ingram has a theory that there are five types of people who come to live in Nicaragua: those who are running from their lives back home; "tree-hugging liberals;" those seeking good, cheaper lives; single, elderly women; and con artists.

Ingram says he sees a new trend of with elderly women who find it difficult to live comfortably on a single income back home. Many of them are widows who can get more for their money in Nicaragua, he said.

A relative safe haven

Ingram is 79 years old and lives off Social Security and a retirement pension, spending $500 to $600 per month. Initially he immigrated to Costa Rica, but after being robbed at gun point, he moved north to Nicaragua.

The Lynches and Ingram said they had negative views of Nicaragua before migrating there. "We thought everybody was shooting at each other," Jim Lynch said.

The Economist in 2012 called Nicaragua a surprising safe haven in Central America, despite being one of the poorest countries in the hemisphere. Homicides stood at 13 per 100,000 people for the previous five years, while bordering Honduras had a murder rate of 82 per 100,000 residents in 2010.

While petty theft is relatively common in the tourist towns of Granada and San Juan del Sur, the foreigners who call Nicaragua home said they don’t live in fear.

The Lynches have experienced burglaries in Granada but the items stolen were Jim’s deodorant and the gas tank for their stove.

Andrea Pellegrino said expats sometimes become targets because locals think they are wealthy. "They think we have it all. It’s a third-world country and people are very opportunistic," he said.

Real estate boom

The relatively low cost of living, low crime rates and easy lifestyle have ignited the real estate market, driving prices higher in cities like Granada and San Juan del Sur.

Darrell Bushnell is an immigrant from North Carolina who is referred to as the gringo mayor by his fellow expat friends. He has lived in Nicaragua with his wife since 2006 and writes about life in Nicaragua in a blog.

Bushnell believes the majority of foreigners who are purchasing property in Nicaragua are investors and speculators, while only a fraction are expats buying homes. "We are already seeing the lower-priced oceanfront lots disappearing," he said.

Anyone can purchase property in Nicaragua, including tourists. The purchasing process is similar to that in the United States; however, real estate agents do not require any certification and there is no database of what properties sell or the amount they sell for.

Mike Cobb is an expat and chief executive officer of the ECI Leadership Team, a real estate company building developments along the coast for retired foreigners.

Along with rising property prices, Cobb says the level of services, activities and restaurants also is on the rise, contributing to a general improvements in the economies of Granada and San Juan del Sur.

Cobb says about 50 percent of expats rent their homes instead of buying and that those who buy are mostly concentrated in Granada and San Juan del Sur.

Chale Espinosa, a local Nicaraguan who invests in real estate, credits foreign investors with helping to rejuvenate Granada by attracting entrepreneurs who have started restaurants and hotels, bolstering the tourism trade.

The impact was laid out in a letter written by the mayor of Granada, Eulogio Mejia Mareneo, to Bushnell, which he posted on his blog in 2012.

"The city is investing more than 30 million dollars over the next three years of my government in projects that will enhance infrastructure, public services, and sanitation, in order to promote and bolster tourism as the principal engine of our economy," the mayor wrote.

Many in Nicaragua pin their economic hopes on tourism. In the rural area of Tortuga, a small primary school has built a space to teach English and computer classes to prepare students to work specifically in tourism.

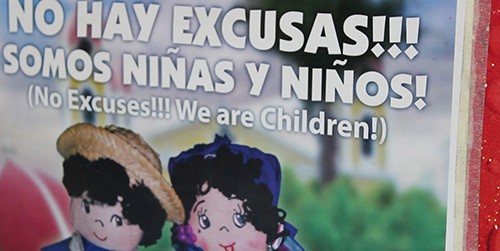

In San Juan del Sur, expat Dyani Makous teaches English to children after school. Her organization, the Barrio Planta Project, offers classes ranging from crochet and dance to working with computers.

Makous was raised in Pennsylvania and migrated to Nicaragua in 2008. She says she wanted to teach locals English so they can work in the growing tourism industry.

Makous hopes her programs will build a bridge between the local residents and the tourism industry so they can participate and prosper while preserving the Nicaraguan culture.