Canal opposition leader ready to fight for the land in Nicaragua

By Miguel Otárola / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published June 17, 2015

RIVAS, Nicaragua – The emerging national leader of the protest movement against Nicaragua’s proposed Grand Canal answered the door minus a shirt and with his pants unbuttoned.

“Come on in,” Octavio Ortega said in Spanish. “I’m just finishing getting dressed.”

Ortega walked through the main room of the Foundation for the Municipal Development of Rivas, the environmentally-focused nonprofit that he heads. He stepped inside a small room where he lives and sleeps, emerging with a belt, a button-down Ralph Lauren shirt and a bottle of cologne.

Positioning himself in front of a full-length mirror, he finished dressing and then sat down at his wooden desk. He pulled out a black brace and wrapped it carefully around his left wrist, the one that was injured when he was beaten and arrested while leading a protest nearly three months earlier.

Finally, he opened the bottle of cologne and sprayed it in the general direction of his armpits, creating puddles of liquid on his shirt. On this early March morning, Ortega was now ready.

Ortega is accustomed to getting ready on the run. He hadn’t been home in 15 days and missed seeing his 16-day-old grandson who lives just five blocks away.

But according to him, nothing is too inconvenient if it advances the movement he heads opposing the construction of an inter-oceanic canal in Nicaragua.

Ortega, 54, is the visible force behind the National Council in Defense of Land, Lake and Sovereignty, a coalition actively opposing the passage of Law 840, authorizing the canal and approved by the Nicaraguan National Assembly in June 2013.

The proposed 173-mile canal would start near Brito on the Pacific Ocean west coast, cut through Lake Nicaragua and exit near Punta Gorda into the Caribbean Sea. Law 840 gives the Hong Kong Nicaragua Canal Development Group, a company headed by Chinese billionaire Wang Jing, a 50-year concession to build and operate the canal.

The government says the project will create 50,000 construction jobs and 200,000 other jobs. Supporters say the canal will energize the economy in a country ranked as the second poorest in the western hemisphere behind Haiti and the poorest in Central America.

The project, which officially broke ground on Dec. 23 of last year, has faced strong opposition from many in the country, including local Nicaraguan farmers — campesinos — whose land lies within the proposed canal zone.

Opponents contend the law cedes too much control to the Chinese company. Thousands of people could be displaced by the canal construction, and there are no plans to help them relocate. They worry about the impact on Lake Nicaragua, which, although badly polluted in some areas, is still a source for drinking and irrigation water for the agriculturally dependent region. All of that is compounded by what opponents say is too much secrecy, too little planning and an overall lack of transparency by the Nicaraguan government and the Hong Kong-based HKND group.

The opposition movement

“This senseless government wants to destroy Lake Nicaragua,” Ortega said. “If the third World War will be fought because of lack of fresh water, then we would be losing our most prized possession.”

With the Ortega-led council’s help, campesinos and urban dwellers have participated in more than 40 anti-canal protests across the country, the first on June 13, 2014, according to the anti-canal group Nicaragua Sin Heridas.

While many of the marches have been small, they have drawn more than 10,000 people. Most have been nonviolent, but one in southeastern city of Tule in December turned ugly. It was there that Ortega said he was beaten so badly he needed help to crawl into his bunk during the seven days he was jailed.

The incident propelled him into notoriety as a leader willing to put his body on the line for the cause; his followers now treat him as something of a hero.

The reverence was on full display just after Ortega finished dressing on this Monday in March. Before 9 a.m., a young man and woman, both 22 years old, came in through the open door of the FUNDEMUR office. The woman, Maricela Riguero, promptly sat down next to Ortega and began to clip the nails on his damaged left hand.

The two had more on their minds than Ortega’s grooming. They were there to receive letters from him that will cut tuition costs in half at Hispanoamerican University, a partnership between the university and Ortega’s FUNDEMUR organization. Riguero said he wants to study hotel and tourism administration, and Herty Centeno said he wants to study systems engineering.

Like most people who come to Ortega’s office, Riguero and Centeno are involved in the opposition movement against the canal. Centeno takes photos of the anti-canal marches and uploads them to social media accounts. Both view the canal law as unconstitutional and say it is an attack on land rights.

“I wouldn’t want (developers) to take anything from where I live, where I was raised,” Riguero said. “And that’s what the people are not in agreement with, for them to be taken like that.”

Riguero and Centeno look to Ortega for inspiration in their fight.

“I’ve accompanied him on marches in different communities, and he says he has no property that is in danger of being lost. He is out there fighting for Nicaraguans,” Centeno said. “He fights for the good of all, not for him or for something that he will benefit from. People have told him that they are going to kill him, and he has never had fear. This is a man that really loves Nicaragua.”

From the military to the opposition

Ortega spent nine years in active military service. A document displayed in his office lists his official start date as July 19, 1979 — the same day the Sandinista National Liberation Front’s Junta of National Reconstruction proclaimed a new government, effectively ending the oppressive U.S.-backed Somoza regime.

The Junta was headed by current president Daniel Ortega, who became president of Nicaragua in 1984, then lost three elections before re-emerging as the nation’s leader in 2007.

A photo of Ortega — sitting on a green hill, wearing a light army uniform and grasping the handles of a machine gun — hangs on a wall at FUNDEMUR. He fought for the Sandinista government during the contra wars of the 1980s. The Reagan administration supported the anti-Sandinista contras because it saw the new government as a regional Communist threat during the Cold War.

Ortega and his military team did much of their work in Rivas. It was this experience that convinced him to stay there after his military service.

“I loved the tranquility of Rivas, and for that reason I decided to stay there,” he said. “I consider myself a man of Rivas, from the heart.”

He rose to the rank of lieutenant in 1982. He said he should have been promoted to captain within three years, but five years passed without that happening. So he left the country, traveling illegally to the United States and joining the family of his mother’s sister in Virginia.

“I left very angry,” he said. In the States, he secured a landscaping job, working from 1988 to 1996.

Snippets of his time in the United States are captured in one of the photo albums stacked on a metal file cabinet in his office. One photo shows him lying on the beach next to a pier wearing red swimming trunks; in another he is standing in front of the gates to the White House, smiling broadly. He is wearing a white button-down shirt, and he is slightly slimmer, his mustache noticeably thicker.

He returned to Rivas in 1996 to help raise his children. He found himself in a different Nicaragua, with the Sandinistas no longer in power.

Back in Rivas, Ortega founded FUNDEMUR, a non-governmental organization he has presided over for 18 years. Its two main focuses are environmental protection and human rights.

“That was my main involvement: to prevent the pollution of the water in Nicaragua,” he said.

The idea to form the broader land defense council coalition came later, after the canal law was passed. Ortega still bases his work in Rivas, a region where the canal won’t actually cross, but which he thinks could be negatively affected nonetheless.

“What we think will happen is an ecological disaster,” Ortega said. His history with water conservation, support of underrepresented communities and political dissatisfaction put him in the right place to lead those frustrated with the uncertainty the canal poses.

Fears and problems

As he flips through an album of newspaper clippings, Ortega pauses over photos of himself posing with other members of the land defense council and walking in the front lines of a protest march.

“I kept these because I want to make an album,” Ortega said. “I just need to laminate them, but for that I need money.”

For now, he has more important concerns. He points out a splotch of black paint splattered across a window next to his desk, saying it was ordered by the government. Later in the day, when a man walks by the building, Ortega claims he is a spy trying to pick up intelligence for the government.

Also in his office is a large map of Nicaragua that shows the proposed canal route; Ortega has drawn a straighter route on the map. His suggested canal path would cut through just one small community.

“You wouldn’t have the social problem of displacing people,” he said

His route, while politically untenable, was drawn to prove a point.

“Why don’t they do it through there? Because there won’t be a canal,” he said. “What there will be is expropriation of the campesinos’ land. There won’t be a canal.”

Fear of a land grab is the main reason for the opposition movement. Law 840 states that the HKND Group could ask for whatever Nicaraguan land it wants, paying either the government-assessed value or market value, whichever is lower. The land could be used for “all or a part of the project,” according to the canal law.

Ortega isn’t sure the canal will be built, but he fears the land will be confiscated for tourism development. It’s why he and other leaders of the council fear that campesinos will be displaced with nowhere to go.

“(Daniel Ortega) made a law for expropriation,” said Francisca Ramirez, a member of the land defense council who has property in the Nueva Guinea region on the eastern side of Lake Nicaragua and who works closely with Ortega. “So we won’t stop our protests; we won’t stop organizing because the law is still live.”

Ramirez said that when Chinese surveyors escorted by Nicaragua soldiers examined property along the proposed canal route, it shocked many into action.

“There won’t be a canal here,” Ramirez said. “This is the opposition of people who would rather die. Based on that position, the people have lost any fear.”

Peaceful protests turn violent

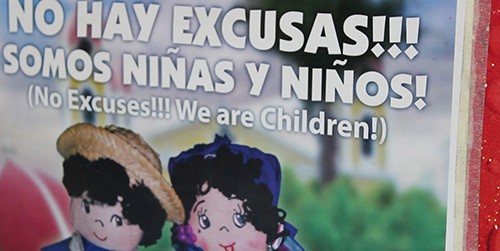

So far, protests against the canal have been mostly nonviolent, consisting mostly of signs and chants telling the Chinese to go home.

But in what became a turning point in the opposition movement, Ortega and other anti-canal leaders were arrested after brutal clashes with riot police on Christmas Eve 2014 in Tule.

“They fractured my arm; they tore my eyebrow and they gave me a beating that to this day I still regret,” he said.

“Octavio was one of the ones hurt and detained,” said Ana Margarita Vijil, president of the Sandinista Renovation Movement, which has joined the movement against the canal.

“If there hadn’t been that (Christmas Eve) protest, we wouldn’t have appeared in the media,” Vijil continued. “Maybe an incautious international investor would have already fallen into this game and started investing.”

How to inform people about the canal law — and convince them to demonstrate — is a main part of Ortega’s job.

He sees social media as a key. Users send him encouraging words and make posters or videos supporting his leadership. He responds by reminding supporters it’s all for the greater cause.

“Our fight is … explaining what is happening and telling them the reality of what we’re living in,” he said. “And the people leave happy, because they know they leave with updated information of what we have accomplished.”

For the remainder of the morning, Ortega visits with a member of the land defense council and landowner in Amarillo who comes in to tell him Chinese surveyors have been sighted, infuriating local landowners. Before day’s end, two others have turned up to give Ortega updates. Ortega, in turn, tells them his plans for nationwide protests to dissuade investors.

“It’s hard,” Ortega said. “But as it’s hard, so it will be our triumph. Because when you speak to the people in a sincere manner, and you look at them in the eyes, and you tell them the truth, you convince with your message.”

Ortega hopes the Nicaraguan protests will lead to something greater than just the end to the canal project: laying the foundation for a true democracy.

“Six months ago, no one could protest in Nicaragua because people were repressed,” he said. “Now, we have 35 marches, and we’ll develop more marches because people have lost their fear to this dictatorship. And when people lose their fear, a change of system can come at any time.”

That idea launches him into a passionate diatribe that conjures visions of another Nicaragua revolt.

“Another Arab Spring could happen here. In the Arab countries, the grandmothers were the ones who started protesting first, with pots and pans. Then came the daughters and the sons, and they asked why they were protesting. Then came the grandchildren, and they popularized it through the Internet — text messages, photos. And then the city squares began to fill with millions of people. And 42-year-old dictatorships were able to be defeated in a peaceful manner.”

“Why can’t we do that in Nicaragua, if we are 6 million Nicaraguans,” he asked. “All ‘they’ have is the weapons; all ‘they’ have is the force. We have the reason. And as long as we have the reason and we don’t have fear the change—”

He spots a man outside his building and stops to flag him down. Ortega hands him a stack of dirty clothes for cleaning.

He takes a breath, pours a glass of orange juice and sits back down to work on the “change” he speaks of so passionately.