Federal agents use advanced technology to identify, track illegal immigration at sea

By McKenzie Manning

Cronkite Borderlands Initiative

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico-- At 2 a.m. on rolling seas and in complete darkness, Brian Sieg and his fellow U.S. Coast Guard crewmen had just plucked 18 wet and cold Dominican migrants from a rickety boat in the Mona Passage, a perennially rough patch of ocean between the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico.

When the migrants were safely aboard the Coast Guard vessel Chincoteague, Sieg approached them with the U.S. government's latest weapon against illegal immigration: a digital camera on steroids.

The biometrics machine is hardly imposing. It has a small, square finger print scanner next to a larger screen that acts as a mini computer for Sieg to type in information. On the back, is a tiny camera no larger than what is currently on smart phones. The camera is also equipped with a flash since interdictions typically happen at night.

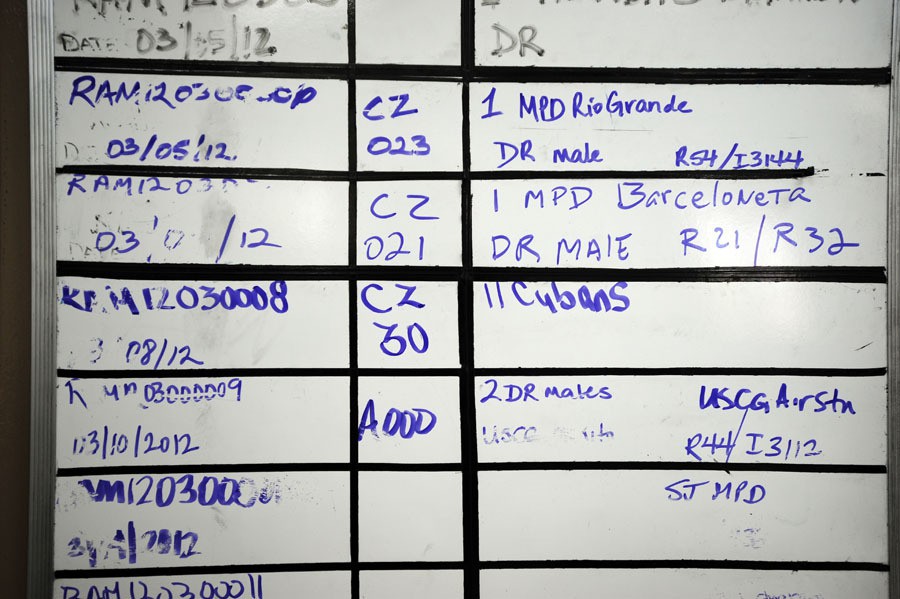

As the migrants boarded the Chincoteague, they were given identification numbers, which are also attached to any personal items that are recovered from the makeshift boat on which they traveled, called a "yola." The identification numbers are used in the biometrics machine along with their names, photographs and fingerprints. Once the biometric information was collected from all the migrants, Sieg then synced the machine to a laptop, which in turn connected to the main database on the mainland United States.

"We can find out exactly if what they're telling us is the truth and if they have any wants or warrants on them," said Sieg, recounting the process hours after the interdiction.

Sieg and fellow crewmember John Koch said that collecting biometrics information at night can be difficult because there is little light to work with. Chincoteague Captain Tim Dolan added, "It can be cold with the wind" at night as well as wet on board the vessel, complicating the goal of the biometrics: to establish a database of repeat undocumented immigrants for potential prosecution.

To get more accurate fingerprints, the migrants are asked to wipe their hands before placing their fingers on the handheld device, trying to get them dry enough.

SLIDESHOW: The U.S. Coast Guard often provides aerial support during migrant interdictions. |

"It's troublesome at times, pulling them out of the yola. And of course they are going to be soaking wet, their hands are soaking wet so we're taking fingerprints and using pretty sensitive equipment to do such a thing," said Sieg.

From the view of a U.S. Customs and Border Patrol helicopter flying in support of the Chincoteague later that day in March, the migrants looked subdued, sitting on the deck covered with blankets as the cutter plowed through three- to five-foot seas. Later, on the return trip to San Juan Bay, after the Chincoteague had delivered the migrants back to Dominican soil, the crewmembers recounted the mission.

"We identified that there were eighteen persons on board, sixteen of which were from the Dominican Republic and two were Haitian nationals. There were no immediate medical concerns. A few were dehydrated from making the trip from the Dominican Republic," said Dolan.

During an interdiction, migrants are loaded on board in twos and after Coast Guard crew members collect the biometrics information, the migrants are given water and blankets, life jackets and sometimes shoes.

"You know usually their shoes and socks are soaked and we also have blankets that we hand out to them and give them a pair of flip flops," said crewmember John Koch.

Once all the migrants are safely on board, it is Dolan's turn to decide how to handle the yola, whether to tow it back to Puerto Rico or destroy it out in the ocean.

"A lot of times these homemade yolas are just not that seaworthy and rather than just leave them derelict we'll destroy them," said Dolan. They destroy yolas by either setting them on fire or machine-gunning holes in the wooden vessels so they will sink.

The Coast Guard believes the Biometrics-At-Sea has helped significantly to reduce the number of migrants who successfully make the perilous journey.

Before the Biometrics-At-Sea program was implemented in 2006, the Chincoteague's protocol would have been to just take all eighteen migrants back to the Dominican Republic. Now, however, with the use of biometrics, they are building, and utilizing, a database that contains information such as whether or not this is a person's first voyage. Typically, those who have tried to come into Puerto Rico illegally will be kept in Puerto Rico for possible prosecution.

This is also how the U.S. Coast Guard and other agencies, such as U.S. Customs and Border Protection, are trying to prosecute ringleaders and smugglers. They have identified smugglers in the past.

SLIDESHOW: The U.S. government uses technology to identify and catalog migrants on land and sea. |

This is not a unique situation for the crew of the Chincoteague. The U.S. Coast Guard claims that by 2007, illegal immigration dropped by 40 percent. By 2008, immigration attempts had dropped by 75 percent overall.

But some U.S. officials concede that the downturn in the U.S. economy, including in the commonwealth of Puerto Rico, has likely done as much as enforcement and interdiction to curb illegal immigration. Economic records also indicate that the recession hit Puerto Rico even harder than any other U.S. state or territory. In January of 2008, Puerto Rico's unemployment rate had risen to 10.7 percent. Just three years later, it had reached 15.2 percent.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Puerto Rico's unemployment rate leveled at 14 percent for both February and March in 2012. And almost predictably, the U.S. Coast Guard has measured an uptick in the immigration trend from the Dominican Republic compared to last year.

The Coast Guard estimates that through August 1,058 undocumented immigrants have attempted to reach Puerto Rico by boat compared with 932 in the 2011 fiscal year.

"We used to apprehend 1,600 [immigrants] a year and it went down to 398 which has been our lowest level to date," said Edgardo Milan, supervisory border patrol agent for the U.S. Border Patrol.

And if the economy continues to improve in Puerto Rico, the illegal immigration trend might rise even more.

"It's just so wide. You can claim the economics too, we had high unemployment, the Dominican Republic has gotten better…there's so many factors you can't say one thing," said Milan.

Back to Top