Border Markets Provide Passage

for Undocumented Immigrants

BY STEPHANIE SNYDER

Cronkite Borderlands Initiative

COMENDADOR, Dominican Republic – Haitians stream through a low-lying metal gate into the Dominican Republic, past uniformed and armed guards who give them only a casual glance.

It’s market day, when Haitians don’t have to present a visa or passport to cross into this capital city, one of the Dominican Republican’s poorest, or into two other Dominican cities, Dajabon and Pedernales.

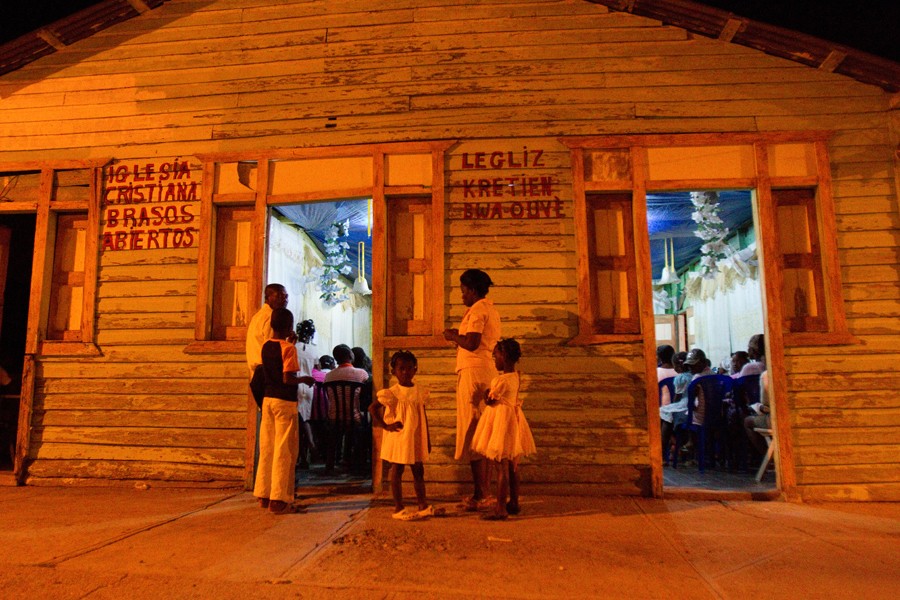

People wait by the door of Open Arms, a Haitian protestant church, in Comendador, Dominican Republic. Photo by Michel Duarte |

But there is a catch: Haitians without documentation are not permitted to travel more than about 100 yards into the Dominican Republic, and they are expected to return to their country by 6 p.m.

Every Monday and Friday, the border between the two countries opens for the simple reason of commerce. Commerce, in fact, links the border towns of the Dominican Republic and Haiti in much the same way that it binds the towns that lie on either side of the U.S.- Mexico border. People cross to sell goods, and they cross to buy them.

Comendador is a city that revolves around the market, and it is a city that would very likely wither without it, said Cruz Dalis Ramon Meran, supervisor of the city’s General Directorate of Migration. It provides a major source of income for both Dominicans and Haitians and creates jobs not only for the border community but for the province as a whole.

“It’s the quickest way for us to survive,” said Meran, who estimates that 2,000 people cross into the town every market day.

But the economic gulf between Haiti and the Dominican Republic – where the average Dominican earns seven times more than the average Haitian – means that some Haitians who cross the border on market days never return. They disappear into the Dominican Republic, squeezing into poor bateyes in crowded cities like Santo Domingo or Santiago or settling near plantations where they can find work.

Some come because they have lost their homes and livelihoods in last year’s earthquake; others are escaping cholera outbreaks in Haiti. Virtually all are fleeing poverty. And because they are a cheap source of labor, Dominican businesses welcome them.

SLIDESHOW: An eclectic assortment of merchants and bargain-seekers

congregate at this market near the border. |

Undocumented Haitian migrants work in agriculture, tourism, construction and other industries, “which now make a lot of money on cheap Haitian labor,” said Bernardo Vega, a former Dominican ambassador to the U.S. and a prominent economist.

But unlike the U.S., the open borders on market days provide easy access into the country. There is no need to hire a coyote or risk a dangerous desert crossing: A Haitian simply waits for market day, then hopes to avoid teams of Dominican military, police and border security agents that scour the countryside, set up checkpoints and search buses.

Many slip through, according to Adolfo Mercedes Medrano, head of customs at the Comendador border crossing.

A United Nations soldier checks the papers of Haitians crossing into the Dominican Republic to trade in the local bi-national market in Comendador. Photo by Michel Duarte |

“The widespread border facilitates the penetration of Haitians, so it is very difficult for us to control (immigration),” he said.

Border enforcement is made even more difficult because some illegal immigrants pay off military police to avoid being sent back to Haiti, according to a 2010 report by Nuestra Frontera, an organization whose goal it is to create economic opportunities along the border.

Others are legal when they cross into the Dominican Republic, but, as is the case with many illegal immigrants in the U.S., they overstay their visas.

That’s what Jean Ludovie Louissain did in 1978. Louissain had a six-month visa to work in construction and stayed on in Comendador. Like thousands of others, he lives without documentation, working and living under the official radar.

When it came time to register his two young daughters for school, Louissain was afraid that his last name – distinctly French – would flag the family as foreigners and the school would refuse to enroll the children. So he registered them under a Dominican surname instead.

While pleased that his daughters are in school, Louissain laments the loss of his family name. He has been in the country for more than 30 years, so why, he asks, can’t he become a Dominican citizen?

Haitians, he said, are no more than “material” for Dominicans to use.

New Market Restrictions

Security along the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic was tightened in late 2010 after a cholera outbreak in Haiti was confirmed in mid-October. By the end of May 2011, 321,000 cases and 5,300 deaths were recorded, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Officials in the Dominican Republic, fearing the outbreak would spread to their country, began mass deportations in the country’s larger cities and temporarily shut down the bi-national markets in Comendador, Dajabon and Pedernales.

When the market re-opened in Comendador in December, it took a different form. The local government set up a temporary market in a compound just a few feet past the gate between the two countries. Undocumented Haitians now must do their buying and selling there, rather than traveling a few miles further into the heart of the city, where the main open air markets are situated.

As a result, fewer people are coming across the border on market days, and business for both Haitian and Dominican vendors is suffering, said Meran, the migration supervisor.

“The restrictions affect the vendors a lot because people used to come from all over Haiti to buy and sell goods,” she said. “Less people are coming now.”

Dominicans are especially reluctant to come because of concern about cholera, Meran said.

Rosita Cabrera, who sells bedding and clothing at the primary market in Comendador, said she and other Dominican vendors stay away from the border market. “The market at the border is narrow, dirty and dusty,” she said. “If we go there, we’re going to get cholera faster.”

Cabrera is paying a price for her precaution. Her sales have fallen significantly since the cholera outbreak because the majority of her customers were Haitians crossing the border.

“Without the Haitians, we are nothing,” she said.

Haitian Vendors

In addition to the economic importance of the markets to its businesses, the government of Comendador relies on the markets for direct revenue.

A wide range of merchandise is sold at the bi-national market in Comendador, Dominican Republic. Photo by Michel Duarte |

The city auctions off the main market each year to local Dominican businessmen, who then have the right to control it and collect taxes from vendors.

While Dominican vendors are typically taxed 50 to 100 pesos per market day, Haitian vendors are taxed 10 to 20 times that amount, depending on the amount of space they use, a practice that was confirmed by several Dominican vendors, although fearful Haitian vendors declined to comment.

On a day in March, when Haitian vendors, who are predominately women, were unable to pay the tax, a group of Dominicans working for the market owner, led by “el cobrador,” or the collector, confiscated their merchandise and stuffed the items into sacks.

Cabrera said few speak up about the inequitable system or the way Haitians are treated.

“If I speak the truth, I am hated. This is what happens here in this town,” she said. “If you talk about what’s happening, they hate you for your entire life.”

Medrano, the head of customs, along with Comendador Assistant Governor Abraham Nova, denied that there are problems.

“Here in (Comendador), if you go through the street, there are more Haitians than Dominicans – no one is offended and no one is trampled on and no one is mistreated,” Medrano said. “There may be particular cases, but in broad terms, there is no Dominican mistreatment of Haitians.”

Border Policy

The problems the Dominican Republic faces in trying to control illegal immigration are not unlike those in the U.S., Medrano said.

“The United States has strict security so that all Mexicans that want to come to the United States – without documentation or without permission – can’t cross,” Medrano said. “In a way, that’s the same as what we have here in the Dominican Republic.”

And whenever there are great disparities in income, as there are between the U.S. and Mexico and between the Dominican Republic and Haiti, people will keep trying to cross, he said.

Medrano said his country can no more support unlimited immigration than can the U.S.

“If the door is opened, everyone will want to come here,” he said.

But Rosario Espinal, a Dominican sociologist at Temple University in Philadelphia, said that simply trying to keep people out ignores the complexity of the situation. The border is too porous, the two countries are too economically intertwined and there are already too many Haitians living in the Dominican Republic for that to work, she said.

“What you have is an immense population of poor people who happen to be immigrants who don’t have rights, and the (Dominican) system itself is unwilling legally and unable socially to integrate them,” Espinal said. “This is a formula for disaster.”

.jpg)