Dark Skin and ‘Strange’ Name Lead to Landmark Ruling

BY JOSHUA ARMSTRONG

Cronkite Borderlands Initiative

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic – For eight years, Violeta Bosico fought for her name and a permanent place in this country.

But she still doesn’t like people to know who she is.

Bosico was one of two girls at the center of an international court case hailed as a landmark for stateless people – those not recognized as citizens of any country. After eight years of legal battles, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled in 2005 that Bosico and Dilcia Yean, both born in the Dominican Republic of Haitian ancestry, were unfairly denied citizenship.

But in the Dominican Republic, which shares a border with Haiti, the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere, any threat to the nation's ability to police immigration – real or perceived – raises passions among its citizens.

“There was a point where the case and the topic became very contentious in the country,” said Sonia Pierre, founder of the Movement of Dominican-Haitian Women, which helped Bosico and Yean, “especially because there was this whole myth created around the case that it was meant to do damage to the Dominican Republic.”

So neither Bosico nor Yean has ever been publicly photographed. They remain highly guarded to protect themselves from being targeted by nationalist extremists.

Bosico, now 26, clenches her fist as she talks softly about the judgment. “This was not just about me," she said through an interpreter. "This was important to a lot of people.”

Six years after the ruling, the Dominican government has paid $22,000 in damages: $8,000 to each girl and $6,000 for their legal fees. It arranged a publication of the facts of the case in a national newspaper. And it gave Yean and Bosico citizenship.

SLIDESHOW: Violeta Bosico, a 26-year-old Dominican citizen, reflects on her controversial and contested personal history. |

But the government has not taken the more far-reaching steps that might help remedy the problem of statelessness in this Caribbean country of nearly 10 million. The judgment requires a public apology, which has not been issued, and broadly calls for reform in Dominican citizenship laws that would prevent a person from becoming stateless.

Jose Angel Aquino, a top official in the Junta Central Electoral, which issues domestic identification documents, said the human rights court misconstrued Dominican laws when it ruled that the girls' proof of birth in the country should have been enough to prove their citizenship. He said Yean and Bosico should have been granted birth certificates not because they were born in the country but because their mothers have Dominican citizenship. This is a major rift between the Dominican government and the court.

“Clearly, there is a decision of the court that we do not agree with and it is not in agreement with our legal and constitutional disposition,” Aquino said in Spanish. “And that is that the court says that the situation of the parents cannot affect the children.”

International human-rights advocates favor birthright citizenship, which guarantees rights to children of immigrants, no matter their legal status. And for decades, the Dominican Constitution was interpreted to guarantee citizenship to those born on Dominican soil. But as Haitian immigration increased, the Dominican government began to move away from that interpretation and, in some cases, sought to retroactively deny citizenship rights to Dominicans of Haitian descent. This touched off a number of legal battles, including Yean and Bosico's.

Limited Impact

The court ruling in their case, while a victory, appears to have had limited impact. Indeed, an estimated 90 percent of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ rulings has not been enforced, raising questions about the effectiveness of the court and its parent, the Organization of American States.

The Inter-American Court is the top level of the OAS's human-rights system. Based in San Jose, Costa Rica, it has an annual budget of slightly more than $3 million – half from the OAS, the rest donated by governments and organizations. Human-rights advocates see it as a court of last resort without definitive remedial powers.

VIDEO: Two women share their harrowing tales of how they tried to prove

their Dominican citizenship. |

“In this system, we're talking about the worst of the worst cases being handed to a court that has no army, that has no coercive possibility of enforcing its decisions,” said Roxanna Altholz, associate director of the International Human Rights Law Clinic at the University of California, Berkeley, and Yean and Bosico's lead attorney. “It is frequently questioned by states.”

At the top level of the OAS, the Washington-based General Assembly, a single ruling rarely spurs major dialogue. The Dominican Republic's OAS ambassador at the time of the Bosico-Yean ruling, Roberto Alvarez, said it had no effect on his diplomatic business in the organization.

But the Inter-American court and its sister commission have a large influence on governments, he said, and the court's influence could be dramatically increased if all OAS members agree to its jurisdiction.

The U.S., Canada and most of the English-speaking Caribbean countries have not ratified the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights, which would put them under the court's jurisdiction. When the court was created in 1979, President Jimmy Carter signed the pact, but the Senate has never ratified it.

“You have a gulf that exists between the Latin American countries and the common-world countries that do not have a stake in the system,” Alvarez said. “That gulf is becoming wider over the years because the decisions of the system only apply to countries that have accepted the jurisdiction of the court.”

The court also faces a rising caseload while relying on unpaid judges and a donor-dependent budget. From the court's founding in 1979 until 2002, a total of 49 cases were submitted. From 2003 to 2010, the court received 102 cases. Sixteen alone were submitted in 2010, the most ever in a single year.

Despite those troubles, Altholz and others involved in the Dominican case say the court's judgments are important tools in fighting human rights problems. In most cases, it takes many rulings and incidents for an issue to spur public and international attention and action.

“If you look at it as a snapshot, it's quite a depressing picture, but the arc of justice is long,” Altholz said.

Violeta Bosico is concerned about her safety since taking her citizenship case to court. Photo by Brandon Quester |

Francisco Quintana, a deputy program director and litigator for the Center for Justice and International Law, said the Bosico-Yean judgment "is really important because it’s the starting point, the stick that we use to measure the application of the law."

People who are not recognized as citizens of any country are, in effect, stateless, lacking the basic rights and recognition that governments guarantee. In a legal sense, they do not exist. This is especially true in the Dominican Republic, where a certified birth certificate is required to go to universities, get jobs or marry.

A Proud Citizen

Bosico was once stateless, but now she has her name on a Dominican birth certificate and is proud of that name – Haitian roots and all.

“When I was young, I would always wonder, ‘Oh, my God, how am I going to say my last name in public?’ because I know that I’m going to be made fun of or pointed at,” she said through a translator. “But then one day I said, ‘No, this is my last name. I can call myself what I want. It's mine and it's what I'm going to say everywhere I am.'”

Today, Bosico attends a university in this capital city, spending several hours on public transportation to and from her home in Batey Palive, where she lives with her mother, Tiramen.

Bosico’s eyes are alert, and she wears a shy smile that can grow surprisingly wide. She also is very dark-skinned, and that may have been a problem on March 5, 1997, when she and an infant named Dilcia were sent away from a civil registry without birth certificates. They had been rejected before, but this time they were accompanied by Genardo Rincon Miesse, a lawyer.

What happened next depends on whose testimony is correct. Thelma Bienvienidas Reyes, the registrar, said Miesse never gave her identification documents for the girls' parents. Miesse said he did and that Reyes commented on the girls' “strange” and “Africanized” names.

The case first went to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights – another arm of the OAS human-rights system – which oversaw the Dominican Republic until the country came under the Inter-American Court's jurisdiction in 1999.

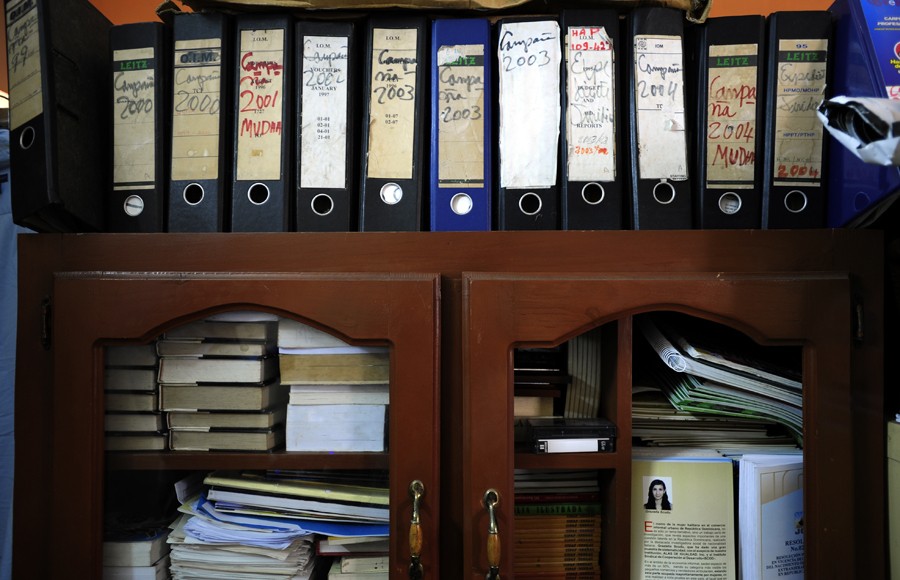

At the center of this effort on the girls' behalf were Pierre and her Movement of Dominican-Haitian Women, known by its Spanish acronym MUDHA. From the time of her rejection, Bosico was a regular in MUDHA's drafty office about a half-mile north of the Caribbean Sea, and she made friends with many of its staff.

"They were very patient and they explained to me step-by-step what was happening,” said Bosico, who was 11 when the case started. “They also explained to me – and I was able to understand – that this was not just about me, and there were a lot of people like me and that this was important to a lot of people.”

When MUDHA committed the two girls' names to court documents, it tried the girls’ names and their connection to the case as quiet as possible. The girls and their parents were shielded from being photographed by media and international organizations.

Pierre said she feared retaliation from Dominicans who oppose birthright citizenship. Even a suggestion of violence could keep people from speaking out in the future, she said.

The ages of the two girls presented unique challenges. Yean, just a toddler when the case was accepted by the court, was especially vulnerable, and not just physically. At one point, Pierre said, Yean told a psychologist that she felt different from the other children and didn't want to have Haitian roots any longer.

Bosico, meanwhile, was maturing rapidly and running out of ways to get an education. At 14, she had to attend night school with adults for a year until she received her birth certificate, which allowed her to return to school in the daytime with students her own age.

Bosico said she no longer fears an attack, but she still does not want to be photographed. Her mother is more worried.

“She walks around on her own,” Tiramen said through a translator. “She goes to school, usually by herself, so I fear for her life.”

Tougher Citizenship Laws

Less than a year after the September 2005 judgment in the girls’ case, the Dominican Supreme Court upheld a revision to citizenship laws that classified illegal immigrants in the same manner as foreign diplomats and tourists – as people “in transit.”

In 2010, the country’s constitution was amended to define citizenship by parental status: If one parent is Dominican, the child is Dominican. But if a child is born in the Dominican Republic to parents who are not citizens, the child no longer has citizenship rights.

The Dominican government is working with some longtime immigrants to gain legal residence, Aquino, the JCE magistrate, said. He was careful to note, however, that not every undocumented person will qualify – only those who were registered legally in the eyes of the government.

“We are proposing that these people in this circumstance regularize their birth certificates so that they can have full rights and, in spite of these irregularities, they can access the benefits of Dominican law without limitation,” he said.

David Baluarte, a former legal counsel for Yean and Bosico, said such programs address part of the problem. But “I think there needs to be a lot of attention and focus on that and support for the Dominican Republic to ultimately do the right thing,” he said.

Some Dominican officials have begun to focus on the problem. In late July, JCE magistrate Eddy Olivares said in a televisions interview that the children of Haitian immigrants should be given identity papers — pointing out that many of them came to the country through labor treaties with Haiti. Olivares also said that the Dominican immigration agency, not the JCE is should be take the lead in deciding whether someone is in the country illegally.

Meanwhile, citizenship cases against the Dominican Republic are mounting in Inter-American human rights bodies. The commission has declared three cases against the Dominican Republic admissible and applied for one of them to be heard by the court.

If the court continues to rule against the Dominican Republic, the country's problems are more likely to be recognized at the top level of the OAS, said Alvarez, the former Dominican ambassador.

“One case by itself does not have that impact unless there are specific conditions in the case that have far-reaching implications,” he said. “By and large, unless you have cases that point to a pattern in a particular country, it's highly unusual that you would have an immediate impact on the political organs.”

Violeta Bosico displays files from her case. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that the Dominican government violated basic human rights laws by denying Bosico a birth certificate. Photo by Brandon Quester |

And if judgments have broad remedies, like the legal reforms ordered in Yean’s and Bosico's case, they can provide a framework for a country to solve its problems when the time comes, said Thomas Antkowiak, a former senior attorney in the Inter-American system.

“Many studies have shown that what victims want most is justice and recognition from the state, and these remedies – like apologies, recognition of responsibility, publishing the judgment, rehabilitation – they go more directly to those needs,” he said.

But even without recognition from the government, judgments can have long-lasting effects, such as the $8,000 paid to Bosico. With that money, Bosico has become a university student. Now, she hopes her story will inspire others without citizenship to persevere.

“I do believe that the more people hear about it … that maybe can help,” she said.