Illegal Haitian Workers in Demand

BY DUSTIN VOLZ

Cronkite Borderlands Initiative

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic – Carlo Collin knows his story is a familiar one. In 2005 when he was just 15, he emigrated from Haiti to the Dominican Republic to find a job and a better life.

Today, Collin works six days a week in construction for what he calls an unlivable wage in an industry that employs primarily Haitians, many of whom, like him, are in this country illegally. Because his passport has expired and his dark skin identifies him as Haitian, Collin lives in fear of being caught and deported.

He said he’s been detained seven times by Dominican soldiers while crossing the porous Haiti-Dominican Republic border. He has paid bribes as high as 500 pesos – about $13 – to military guards at immigration checkpoints on the road to Santo Domingo in order to be allowed back into the country.

“When you see (the military guards) your heart is scared,” he said. “If you don’t have money they will call immigration and send you back to Haiti.”

Collin stays in the Dominican Republic so he can send money home to his family. Finding a job in Haiti these days, he said, is almost impossible.

In fact, more Haitian immigrants than ever have crossed into the country looking for work and refuge since last year’s devastating earthquake near Port-au-Prince. Government officials have estimated that the number of Haitians living in the Dominican Republic increased by 15 percent following the earthquake and they now account for more than a tenth of the nation’s 10 million inhabitants.

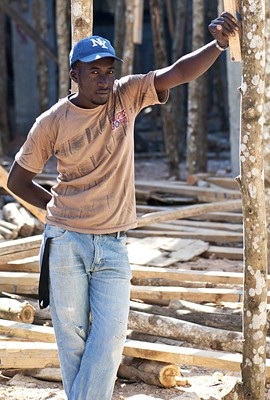

SLIDESHOW: Carlo Collin earns a meager wage working construction to support his family in Haiti. |

Although there is a long history of strained relations between the two countries that share the island of Hispaniola, the Dominican Republic was the first country to provide Haiti with humanitarian aid and to help with rescue efforts after the disaster. U.S. President Barack Obama praised Dominican President Leonel Fernandez during a White House visit last July, saying the Dominican Republic’s response “saved lives, and it continues as we look at how we can reconstruct and rebuild in Haiti in a way that is good not only for the people of Haiti but also good for the region as a whole.”

But while demand for cheap labor keeps many Haitians employed in the Dominican Republic, increased immigration is placing unbearable strains on a country struggling to provide health care, education and social services to its own residents.

Earlier this year, a cholera outbreak in Haiti triggered an aggressive resumption of immigration raids and deportations of immigrants following a one-year moratorium after the earthquake. Government officials reported nearly 7,000 Haitians were deported through mid-March. In May, new outbreaks of the cholera threatened to exacerbate the issue.

To some extent, “compassion fatigue” has set in as more and more Haitians have entered the country in the year following the earthquake. Dominican immigration director Sigfrido Pared rebuked requests from human rights groups such as Amnesty International to halt deportations because conditions in the poorest country in the western hemisphere are still so bleak.

Dominican officials are well aware of the lack of improvement in Haiti but insist there’s only so much support they can provide their island neighbor.

“The solution for Haiti is not that they immigrate to the Dominican Republic, just as the solution for the Dominican Republic is not that we immigrate to the United States,” said Jose Angel Aquino, magistrate of the Junta Central Electoral, the country’s central electoral board responsible for issuing legal documents to citizens. “The solution is that here and there we build more democracy, more institutions, more development for our people.”

Human rights groups are especially incensed that immigration police make no distinction between undocumented Haitians who have just crossed or those who have lived and worked all their lives in the Dominican Republic.

“Deportations are being used as a blunt instrument to regulate migration when it is by no means clear that the people being deported are those people who recently entered the country,” said Dominican-based author and migration researcher Bridget Wooding.

Wooding said that amid tough rhetoric, there is “an open secret” that exists within the Dominican government and among the Dominican people regarding migrant labor. They understand that key industries – construction, agriculture and tourism, for example – rely heavily on cheap Haitian labor. As a result, government officials straddle the fence between appeasing ultranationalists who call for a stricter border policy and satisfying business and economic interests deeply invested in maintaining the status quo.

“There’s always been complicity on both sides in terms of how people can cross,” Wooding said. “The informality of crossing comes to be seen as completely normalized. It’s part of the culture.”

Bernardo Vega, a prominent Dominican economist and historian who served as the country’s ambassador to the U.S. from 1997 to 1999, agreed that the complicity is rooted in economic interests.

Polimet Poleus takes a break from working on the construction site of a new apartment complex in Santo Domingo. Photo by Lindsay Erin Lough |

“We don’t want them, but we need them,” Vega said. “The politicians say we don’t want them. But the economy needs them. And there are no jobs in Haiti. There’s a great difference between the political discourse and what the law says and what happens in practice.”

Despite the immigration crackdown, Vega believes that Dominicans are relying on Haitian labor more than ever. Until about 30 years ago, most Dominicans were rarely exposed to Haitians because they largely lived in desperately poor rural shantytowns called bateyes, located outside the cities close to the sugar cane fields where they worked.

As the country has become more urbanized and the economy more diversified, Haitians have moved to the cities, finding jobs in construction, the tourism industry and other labor-intensive fields. Only 20 percent of Haitian migrants now work in the sugar fields, Vega said.

Rosario Espinal, a Dominican sociologist at Temple University, believes this urban migration – compounded by the influx of immigrants after the earthquake – has led to increased animosity between the two groups.

“In the past couple of months, there have been serious tensions in communities where there are many Haitians settled,” Espinal said this spring. “It was a different story decades ago when Haitians were mostly located in sugar fields and for most Dominicans, they were non-existent.”

A comprehensive survey conducted a month after the earthquake found that a little more than 48 percent of Dominicans thought children of Haitians born in the Dominican Republic should be allowed citizenship rights. Only about 42 percent were in favor of the government providing work permits to undocumented Haitians.

Those numbers are slightly higher than what was gleaned from similar surveys conducted in 2008 and 2006, but Espinal, who co-authored the most recent report, said the bump was likely due to post-earthquake sympathy expressed by many Dominican citizens.

Vega, the former ambassador, agreed. For as long as the Dominican Republic has been allowing Haitians to cross the border, Vega said, the country has been expelling them back where they came from – but not fast enough to keep up with the in-migration.

“There’s never been a moment where we’ve had a net outflow of Haitians,” Vega said. “The few that get deported are much less than the numbers who come back.”

The Dominican labor code mandates that 80 percent of laborers for any company must be Dominican citizens, but the law is loosely applied in practice, acknowledged JCE magistrate Aquino. The other 20 percent are supposed to be legal residents from other countries, but in construction the numbers are often reversed: 80 percent to 90 percent of construction workers in big cities are Haitian, legal or otherwise, while Dominican nationals make up the remaining fraction, according to Vega.

The reliance on a Haitian workforce is pervasive in a number of industries, but in construction, it is openly visible and accepted. In fact, the Dominican government itself increasingly employs Haitian laborers.

“All public works construction uses Haitian labor, so the government is a big employer of Haitian labor,” Vega said.

A glaring example is the workforce on the construction of a metro subway system in Santo Domingo, a prime project of President Fernandez’s administration. The underground construction sites are mostly staffed by Haitians, leaving the government with a contradictory message about its immigration policy.

Chiero Ferristal is a subway construction worker from Haiti. He crossed the border after the 2010 earthquake but said he had trouble finding work even with a passport. Eventually, Ferristal got a job working on the subway for 350 pesos – almost $10 – a week. He has been unable to acquire a cedula – a national identity card required of legal residents over 18 – and because of that he has no right to health insurance.

Ferristal and his co-workers, some of them Dominican, toil away in dust-filled underground sites, working without breathing masks to build the subway’s second line. Ferristal and other workers said Dominican and Haitians work together as if they were brothers.

That is unsurprising to former transportation minister and economist Hamlet Hermann who believes the use of cheap Haitian labor is not a matter of racial exploitation but of economic interests.

“Haitians and Dominicans, they deal one with the other and so we are friends,” Hermann said. “But the interests – I mean, military, politicians, businesspeople – they are the ones that violate all the laws to force the (open) migration.”

Ricardo Yand is helping build an apartment complex in downtown Santo Domingo. Photo by Lindsay Erin Lough |

Hermann used to work in the government during Fernandez’s first presidential term from 1996 to 2000 but has since become an outspoken critic of several governmental policies, including the subway project, which Hermann says has cost $1.5 billion thus far. Hermann points to what he calls a double standard with regard to immigration and Haitian labor policy.

“In the building he lives in, the janitors are Haitian,” Hermann said of the president.

The subway’s technicians are Europeans or Dominicans, Hermann said, but the hard, manual labor is done almost entirely by Haitians because they come so cheap.

According to former ambassador Vega, illegal Haitian labor in the Dominican Republic pulls down wages, which contributes to a wide disparity of income in the country. Additionally, a reliance on cheap labor stunts advancements in technology because businesses have no need to invest when the human resources available are so affordable, he said.

Carlo Collin, the construction worker, is a prime example. He earns 600 pesos a week or about $17 in the U.S. And that’s double what most of his co-workers earn: Because he has six years of experience, he is considered more skilled by his supervisors and helps manage other laborers.

“If you’re Haitian, you don’t have any value in this land,” Collin, now 21, said in his native Creole language during a break from renovating an old government building in Santo Domingo. He wipes sweat from his brow as he peeks out from under a purple President “Leonel” baseball cap. His dark eyes appear distant.

Collin says he wants to go back to Haiti because his family is there and he is treated better, but he can’t because there are no jobs, especially after the earthquake. It’s precisely this sort of desperation that many Dominican employers rely on.

“If we had a good president in our country who was helping us, we would never come here to be mistreated, to be looked at like animals, to not be cared for,” he declared.

Collin has a family to support back in Haiti, but no wife or children. He said he is afraid to start a family in the Dominican Republic because his salary wouldn’t be enough to support them unless they moved back to Haiti, where 600 pesos a week can carry a family a lot farther.

“In Haiti, if you have 100 pesos you will eat,” said Collin, adding that what most of his co-workers make – 300 pesos a week – is not enough to survive on in the Dominican Republic.

Like thousands of other Haitians working in the Dominican Republic, Collin sends what little money he can spare to his family in Haiti. As his countrymen struggle to overcome the earthquake devastation that brought what was already the poorest country in the western hemisphere to its knees, Collin works a job he doesn’t particularly like in a country he doesn’t call his own for a wage he can barely survive on.

“The little money I make, it is money to eat only,” Collin said. “You’re obliged to take the money to send it back to family in Haiti.”

William Mejia, one of Collin’s Dominican supervisors on the renovation project, said Haitian migrants are hired for construction work because they have no rights and are therefore cheaper. Most of the Haitian workers don’t have proper citizenship or residency papers, Mejia said, so he sometimes will hide his workers when immigration police raid his construction sites.

Mejia and others like him perpetuate the open secret Wooding speaks of by employing Haitians like Collin who, desperate to support his family, have nowhere else to turn.

Many Haitian workers are employed building a subway in Santo Domingo. Photo by Lindsay Erin Lough |

For his part, Collin says he wants to return home to Haiti some day, but until the country recovers from one of the worst natural disasters in human history, he will stay and work in Santo Domingo.

The hardships that come with being stateless, a phenomenon caused in part by the flood of illegal migrant labor into the Dominican Republic, is something Collin says he has seen too many times to count. Children of undocumented Haitians born in the Dominican are deported back to Haiti, where they don’t speak the language, don’t know anyone and don’t know how to survive in a country destroyed by natural disaster, he said.

The swinging-door migration policy employed by the Dominican government may not be keeping Haitians out, but the high volume entering has put strains on a country ill-equipped to handle many of its own issues. The only solution, said Vega, is for the international community to keep the promises it made following the 2010 earthquake and support the rebuilding of an entire country. Money has been pledged, Vega said, but not dispersed due to a variety of political and economic concerns.

“It’s so easy to start building houses and yet very few houses have been built,” Vega said. “And if there was a huge project to build thousand of houses in Haiti, some of the Haitians that are here would go back to work there.”

That’s something JCE magistrate Aquino agrees with. Problems in Haiti spill over to the Dominican Republic, concedes Aquino, as the two countries are linked by history, geography and economic dependence.

“The most dangerous (thing we can do) is to leave Haiti to the will of God,” Aquino said. “We share the same rivers, the same everything. If Haiti is allowed to be lost to violence, drugs, to the lack of natural resources, this will come back to the Dominican Republic.”

Until the country is rebuilt, Haitians will keep crossing the border to find work in the Dominican Republic, where, devoid of other options, they will continue going through the motions of being deported and paying bribes to come back again. Why? Because anything is better than Haiti, said Temple University’s Espinal.

“There’s nothing in Haiti,” she insisted. “Nothing. There’s no agriculture; there’s no industry. There’s absolutely nothing.”

For migrants like Collin, Haiti is unable to offer even hope.