High Numbers of Maternal Deaths Plague Health System

BY TARRYN MENTO

Cronkite Borderlands Initiative

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic – Abraham’s mother was just 17 when she died. The same day that he came into this world was the day she left.

Abraham was delivered by Cesarean section at Hospital Materno-Infantil San Lorenzo de Los Mina, a bustling public hospital in the Dominican capital city. His mother, Nana Charlie, died from excessive bleeding.

Maternal hemorrhaging is one of the main reasons for the Dominican Republic’s relatively high maternal mortality rate.

But many come too late. In the Dominican Republic, the lifetime risk of maternal death is one in 320, according to UNICEF. That’s almost seven times higher than in the U.S.

Medical experts say a high maternal mortality rate usually correlates to limited medical access. But in the Dominican Republic, skilled medical personnel attend nearly 98 percent of births, only one percentage point less than in this country.

So many women die in childbirth in the Dominican Republic not because they can’t get to a doctor, but because they get there so late – and because they come in such great numbers.

“These hospitals are free,” said Los Mina Hospital Director Pablo Wagner. “And because they are free, people come from everywhere, from all the surrounding villages.”

SLIDESHOW: New and expectant mothers wait to be seen at Los Mina Hospital. |

Wagner said the hospital is equipped to handle 1,500 to 2,000 births a year. Instead, it is handling 12,000 to 13,000 births annually. Many of the mothers are poor, undocumented women who have had little or no prenatal care. Many of these are from Haiti, where the maternal death rate is even worse – three times higher than in the Dominican Republic.

Those are the facts Los Mina deals with every day. So is this one: 24 mothers died in childbirth at the hospital last year. That’s about the same number of deaths per 100,000 live births in the U.S.

To medical professionals in the Dominican Republic, health care is a human right. No woman in need of maternal care will be turned away, regardless of her immigration status or ability to pay.

“We have had always an open door policy that we would take anyone who comes,” said Leonard Ziur, a Los Mina doctor from Cuba who has also practiced in Miami. “We don’t send them back.”

Haitians Flood System

Three strangers and their newborns, just hours old, share a bare, dimly lit room at Los Mina. Water leaks onto the tile floor.

Yirandy Contrera sits on a narrow hospital bed, wearing a pink cotton baby doll dress, her inflated belly still visible beneath the thin fabric. Her newborn son, wrapped in white terrycloth embroidered with his name, lies on the mattress next to her.

VIDEO: Many Haitian women who cross the border to give birth in Dominican

hospitals don’t realize that their children may end up without citizenship rights. |

There is no recognizable chime of a hospital gadget monitoring vitals. No hospital bracelets or visitors’ badges. No call button to ensure a nurse is just a ring away. There are just the familiar cries of infants and the comforting coos of their mothers.

The care is mediocre by U.S. standards, but it is far superior to what is available in neighboring Haiti, and, as a result, pregnant Haitian women regularly cross the border illegally into the Dominican Republic to have their babies.

No one knows how many of them come – only that it’s many and that the numbers have grown substantially since last year’s devastating earthquake in Haiti, which destroyed many hospitals.

“The cost of this hasn’t been estimated because there isn’t a system that counts the total number of Haitian citizens who live in this country,” said Jose Delancer, director of the Department of Women and Children within the Dominican Ministry of Public Health. “How do you count an illegal population, a population that is registered nowhere?”

“The Dominican laws and the Constitution of the Republic guarantee universal access to health care to anyone, no matter their descent, their races, their nationalities, their immigration status,” Delancer added. “We as a health care system are not here to question immigration policies. We are here simply to provide quality services to the extent that our capacities allow us to, to anyone who asks for it.”

Delancer said the Dominican government has budgeted for public health services for 7 million people in a country with a population of 10 million, although wealthier segments of the population mainly use private health care. The undocumented Haitian population is estimated to represent at least a tenth of the population, some who enter the Dominican solely to deliver their babies.

Many of them have never had a pre-natal check-up, and, as a result, doctors are often unable to anticipate problems and are unprepared for complications that could have been prevented.

Approximately one third of Los Mina patients are Haitian and arrive in poor health, said Wagner, the Los Mina hospital director.

“They don’t have a monthly examination, and when they come to the hospital, they come in an awful condition, in a bad situation,” he said. “They are mothers that don’t have the proper conditions to support nine months of pregnancy. They are without nutrition, without education.”

SLIDESHOW: Eriana Alce, 23 and five months pregnant, lives with four young children in squalid conditions. |

Abraham’s mother was one such patient, according to local religious leader Malia Duval and other members of the community who are familiar with the case. When she arrived at the hospital to give birth, she was in poor condition. She was undernourished and battling sickle-cell anemia and wasn’t strong enough to survive surgery. She bled to death after undergoing a Cesarean section.

Language Barriers

More than five months after the death of his mother, Abraham sleeps on a bed in a home in Batey San Isidro, an impoverished community made up mostly of Haitian immigrants on the outskirts of Santo Domingo. Flies drift freely around his head.

SLIDESHOW: One of the poorest neighborhoods in the Dominican Republic reveals both poverty and perseverance. |

With the whereabouts of their father unknown, Abraham and his 2-year-old sister, Annabelle, live in the care of Eriana Alce, a neighbor of their deceased mother. At 23, Eriana is four months pregnant and already has two children of her own. One of them, a toddler, sits on the dirty cement floor, biting and occasionally swallowing pieces of a torn plastic bag.

An immigrant from Haiti, Eriana does not have Dominican citizenship and can’t legally work. Her husband works at a nightclub, but the couple struggle to feed the children they have.

Asked what she is going to do with another baby coming, Eriana replies, “Nada.”

There is nothing she can do.

Like many immigrants from Haiti, Eriana speaks only a little Spanish. Her native language is a dialect of French-Creole, and that presents yet another challenge to health care professionals.

“Usually they come when they are almost at time of delivery,” said Ziur, the Cuban doctor at Los Mina. “They live in Haiti. They get here and they tell you, ‘No, I don’t speak Spanish. I don’t speak English. I don’t speak anything, only Creole.’”

Translators are sometimes available at the hospital, but not always. Ziur said he handles an average of 40 patients a day. In a typical eight-hour day, that’s five patients per hour, and nearly one third do not speak Spanish.

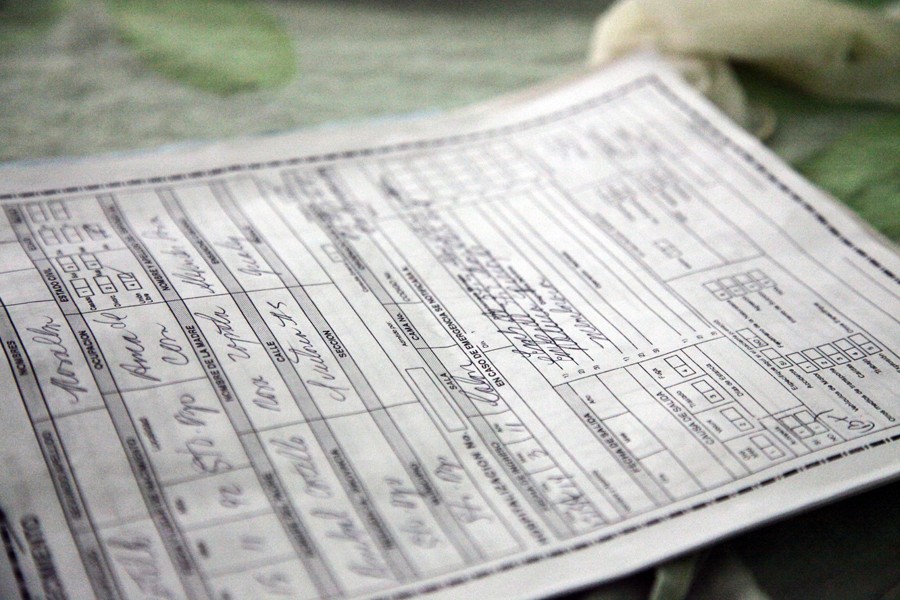

The Dominican Ministry of Public Health is trying to overcome the language problems by adopting a common form for perinatal histories and translating it into Creole. The ministry has disseminated the translated document throughout Dominican hospitals and also has sent the form to Haiti.

Common Problems

The maternal health problems in the Dominican Republic are not unique, and, in fact, many are the same as those facing immigrant populations in the U.S.

Many undocumented women in the U.S. have little or no access to pre-natal care during pregnancy, according to a 2010 Amnesty International report. Private insurance is too expensive, and they don’t qualify for Medicaid because they are in the country unlawfully.

Although U.S. law requires that all women in active labor have access to medical care regardless of immigration status, many arrive at hospitals in poor condition, according to the report. They frequently lack pre-natal care and don’t speak the language.

Medical care for undocumented immigrants is being increasingly debated in the U.S. In Arizona, for example, a bill introduced in the state Legislature last year would have required hospitals to identify suspected illegal immigrants. While those in need of emergency services would get them, the bill would have denied services to others.

The bill failed to pass after hospital and medical associations voiced strong opposition to checking patients’ immigration status. However, state Sen. Steve Smith, a Republican who represents a large district south and east of Phoenix, has said he intends to reintroduce the bill next session.

Such a debate has not yet surfaced in the Dominican Republic, despite evidence that treating illegal immigrants has stretched the health care system beyond its capabilities and even though the two countries – the Dominican and Haiti – have a long history of antagonistic relations.

Ziur is typical of doctors who say that if the Dominican Republic adopted a law requiring hospitals to notify authorities of a patient’s immigration status, he would refuse.

Treating undocumented population may be hurting the Dominican health care system, but not treating people in need would be more painful.

“I will not do it. I will just resist,” he said.

Medical care, he said, is not about policy or politics.

“Your duty’s not that. I’m here to save lives.”