Model city built to help Mexico’s indigenous poor now a ghost town

By Andrea Martinez and Erin O'Connor / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published Sept. 25, 2014

SANTIAGO EL PINAR, Chiapas, Mexico – Children from the school can be heard in the daytime but when class ends the voices in this nearby city die down.

More than 100 houses were built here as part of the “sustainable rural city” project but the people who came to live here did not stay.

Santiago el Pinar was planned as one of four model cities to help the state of Chiapas’ rural poor find better lives. They would have modern conveniences, better schools, access to health care. They would work in a local assembly factory, leaving behind the scattered villages, mud huts and subsistence farming that had sustained their families for generations.

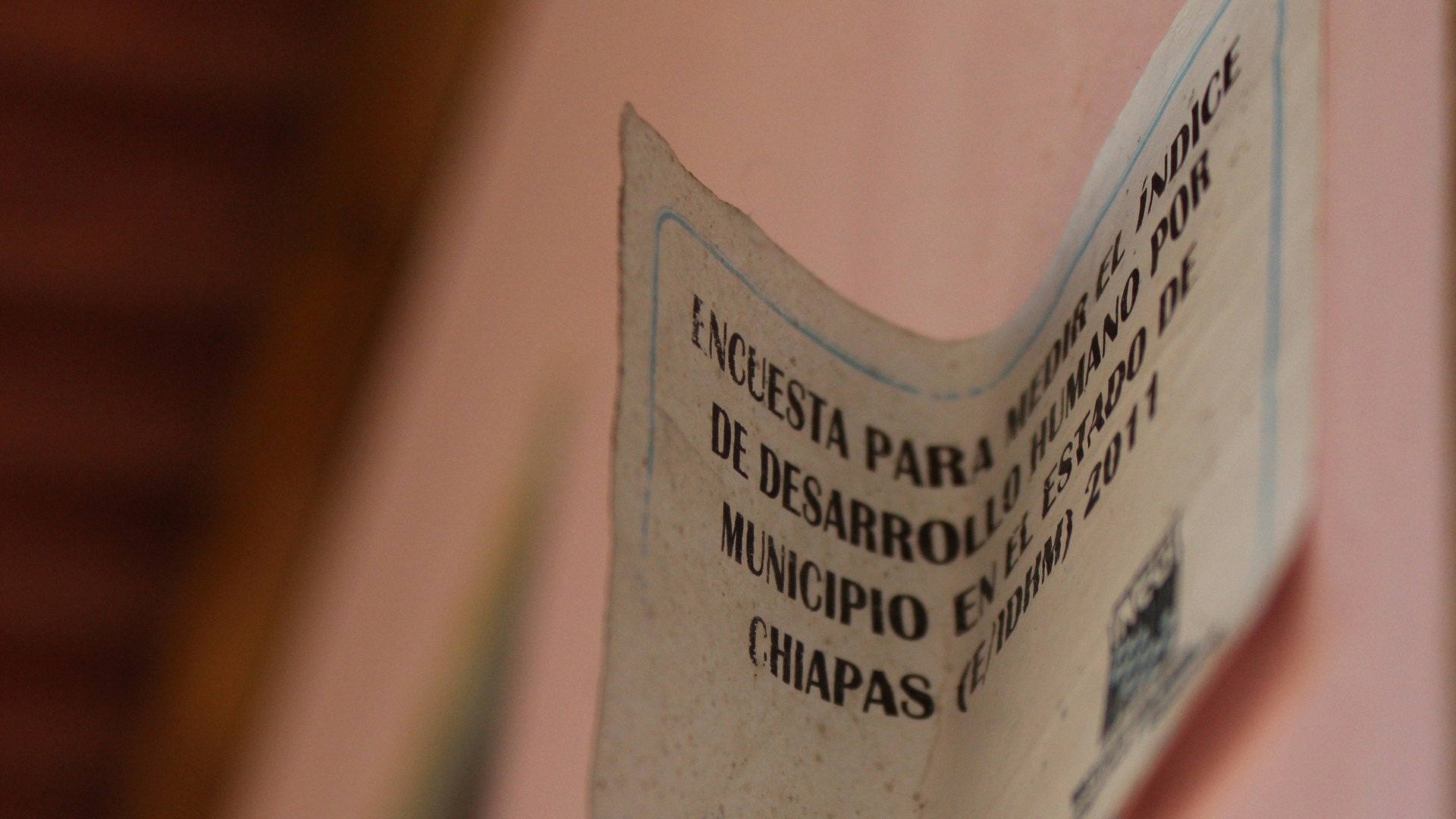

The project was so important that Mexico’s president at the time, Felipe Calderon, personally dedicated it when it was inaugurated on March 29, 2011.

But just three years later, the model city is a virtual ghost town.

The factory has closed. Store gates are shut in the abandoned market. Sidewalks are overtaken by weeds. Houses are empty shells. They have been looted and are missing doors, windows and anything else that could be carried away. And at dusk, the main sound heard in the town is the flapping of the torn plastic of the greenhouse at the top of the mountain that frames the colorful houses built on stilts in the abandoned city.

What went wrong?

The Sustainable Rural Cities Program seemed well-intentioned when proposed by former Chiapas Governor Juan Sabines Guerrero and then passed into law by the state congress in 2009.

“I believe in a program that speaks about population dispersion, that talks about people accessing 100 percent of basic services,” said Alejandro Gamboa, who helped design the program. “It can’t be a bad program, no?”

But critics say that Sabines and his technocrats were ill-informed about the culture and the generational ties of the indigenous people they were trying to help in Santiago el Pinar.

Housing problems

Eighty-six percent of Santiago el Pinar’s more than 3,000 municipal residents are indigenous, descendants of Mayan tribes, a contrast to the populations in the other three locations where the program was carried out more successfully. According to critics of the program, the needs and opinions of the indigenous varied from those of non-indigenous populations, but those differences were not taken into account.

“It’s clear that there was no planning, that there was no previous investigation to understand the situation … the social situation,” said state congress Rep. Alejandra Soriano Ruiz, a member of the leftist Revolutionary Democratic Party (PRD). “You can’t just take someone away from where they are, move them to another place without taking into account the opinions of the people that are going to go live [there] and that are going to be moved.”

But Gamboa, who briefly oversaw the program as the president of the Institute of Population and Rural Cities under Sabines, said that there were attempts to meet cultural needs at Santiago del Pinar, including modifying designs of the homes situated on 3,330-square-foot lots. There, the new residents were expected to live, farm and keep animals.

“When I arrived as president of the institute I had to make many modifications to the design among them, for example, the people of Santiago el Pinar are used to cooking fires. And a cooking fire for them is an important cultural topic because it is where the family gathers. They make their food, that’s the topic there,” said Gamboa in a telephone interview. “The houses had an ecological kitchen inside the homes so I had to cancel that to construct a cooking fire on the small patio that they had so the people could be comfortable with their traditions.”

But the changes were not enough to entice families to stay or even move in to the houses.

“In reality many did not even inhabit them. And others just went for the photo. Others lived there for a while and they returned to where they were accustomed,” said Gamboa. “I think it was the lack of monitoring by the authorities to demonstrate and show them what advantages population concentration has, no?”

The Gomez family, one of the few still living in Santiago el Pinar, had problems with their too small house and cooking space. They built a kitchen on the patio but the cultural need of a cooking fire was not the only reason they continued with their traditional cooking source.

Carolina Gomez, 18, said her family could not afford to pay for the fuel of a gas stove.

“We needed to cook. We use wood and it has to be there in the kitchen … and we always use wood because we don’t have money to buy gas,” said Gomez.

Not only was the kitchen ill-conceived; the homes, which are an average of 430 square feet, were too small for the large, traditional Tzotzil family of the Chiapas highlands.

The Gomez family added patio kitchen doubles as a bedroom for Carolina’s parents. Carolina and her seven siblings use the two bedrooms and living room as sleeping quarters.

Different house designs were used at the three other model “sustainable rural cities” that state officials say are doing well: Nuevo Juan de Grijalva, Jaltenango and Ixhuatán. But the populations in those locations are mestizo – of mixed race – not primarily indigenous like in Santiago el Pinar and have different cultural needs. In addition, residents from projects like Nuevo Juan de Grijalva had worked with the government before, something that architect Cinthia Ruiz who studied Santiago el Pinar, said helped people accept the “sustainable rural city” program.

“On the side of Nuevo Juan de Grijalva, there had been previous relocation experiments in 1987 with the Peñitas Dam and that makes the people be more open and easier to adapt,” stated Ruiz. “The work and attention that was carried out was the same for two completely different communities. And I think that it was an error. They should have considered the differences between the two communities to give them specific attention.”

Francisco Lopez, an engineer with the new administration at the institute that oversees the project, said he did not know why the designs or building materials used in Santiago el Pinar were different.

But despite the sparse occupancy, Lopez said he considers Santiago el Pinar a success. Major infrastructure – roads, a city sewer system, a factory and other economic projects – have been built in the area and only a few modifications need to be made to restart services. He said problems with the program were due to decisions made by the old administration which the new one has been trying to remedy since early 2014.

The handoff of the cities from the state government to the municipal government has left doubt of who is financially responsible for the upkeep of the new infrastructure, Lopez said.

“That is the problem that was happening in the rural cities,” stated Lopez. “There has not been a delivery to the municipalities and the municipalities say, ‘I need money to start those [services] because what they give me is to look after what I already have.’ But all that happened in the immediacy of the past administration, and, as I was saying, there were many things left empty, and that’s the part that we’re restarting.”

Problems between the government entities have left the Gomez family without basic utilities that were promised, like electricity and water.

“Right now there’s no electricity, it’s very low. Like this refrigerator can’t even be plugged in. Last night we didn’t have electricity,” said Carolina Gomez.

The Gomez family were not original residents of the sustainable city of Santiago el Pinar. They purchased their home for 7,000 pesos, about $537, in order to be closer to the city’s school. They have no legal documents to confirm the sale, only a verbal agreement with the original owner.

The sale of the home to the Gomez family was in violation of the sustainable city rules. Ownership was meant to stay in a family for 25 years so that the heads of household could pass on something to their children. It was also meant to prevent those who had already received a house from the government from asking for and receiving another.

But the houses may not last those 25 years, according to Ruiz, the architect who has been studying Santiago el Pinar.

“In optimal climates they should last 50 years, perhaps. But in those conditions where it’s not the optimal climate and with the amount of humidity that they have, I calculate 15 to 20 years at most. No more,” said Ruiz.

The government was aware of the potential construction issues during the building of Santiago el Pinar, but Gamboa says that part of his charge was to try to mitigate the problems quickly in order to populate the city.

“In reality they are houses that are very, very, very badly made. They are not for the location’s climate. But we tried to adapt them as soon as possible to inhabit (them),” said Gamboa.

The structures in Santiago el Pinar have stood for three years and have declined in that time. Lopez said part of the plan to revitalize the city is to reconstruct the houses in that area.

“There the housing is completely deficient housing. So the plan is to totally reconstruct the houses. There, practically, the 105 houses I think it is, have to be all changed,” said Lopez. “The houses that they put in Santiago el Pinar are not in conditions for habitation.”

An economic restart

New houses will not be the only new part of the program at Santiago el Pinar. Recent plans to bolster the economies of each city have been formulated as well. Santiago el Pinar’s factory will be operated under a new plan different to the model used when the city first opened.

Lopez said the new administration is implementing business plans in the sustainable cities, something that was not done before. Previously, the government had been the primary buyer of the goods produced by factories.

They churned out goods like chairs, desks and bicycles but the operational costs were comparable to the cost of goods already made.

Gamboa, the former institute president, conceded the factories may have put some strain on the government.

“The factory is a burden to the state government. That is why it cannot function. A real factory directly benefits the population: jobs, directly and indirectly,” Gamboa said.

He noted that the government failed to develop markets for the products. The government paid for the products to be made and then bought them all, amounting to a double subsidy that is not cost-effective.

“The factory program is a program that originates so that instead of buying a chair that is already made that costs let’s say 10 pesos, you buy the pieces for the chair in six pesos. And you pay four pesos for labor. That is the objective of the factory. But if the government decides to buy the 10 peso chairs then there is no more factory.”

The new administration, however, has plans to push to markets beyond the Chiapas borders and diversify what is produced in factories and greenhouses.

“We need to have the capacity to generate profitability in the market, open market opportunities not just within the state but toward the outside,” said Lopez.

However, the new proposals will require an injection of capital. A proposed investment of 43 million pesos, about $3.5 million, is expected to help revitalize the economies of all four cities by recharging the factories, greenhouses and farms for production. But it was money that did not need to be spent.

Lopez said the failures at Santiago el Pinar “should not have happened if it had been delivered right. And it would not have happened if the person in charge had given a business vision which are the…things that now we’re rethinking. And what the population of the rural cities understands is that under a new plan things can be started again.”

A solid economic base would help those like the Gomez family. Family patriarch Antonio Gomez has vision problems that make it difficult to work in the field but a job in a factory close to his home could give the family much-needed income. These new opportunities would also help Carolina who will graduate from high school in the summer but cannot afford to continue her studies. A job under the plan may be one of her only options for her immediate future.

According to Lopez, these new plans, along with working services, have the potential to help the sustainable cities grow. Services and economic opportunities that are not available in the dispersed locations of Chiapas make the program attractive and Lopez predicts that people will want to move to the cities.

“Without a doubt there is going to be an economy and circulation that is going to generate a different condition,” stated Lopez. “And later there is going to be a demand [to live in the rural cities].”

Waiting on promises

For now, the Gomez family relies on Carolina to make a trip up the mountain to carry down water from a well. But that source is not reliable and the family has no place to store the water Carolina lugs home. When the Gomez family purchased their house, several items were missing, including the toilet, sink and water storage tank.

“It didn’t have anything. It didn’t have a toilet, a sink. There almost nothing left. The rotoplas [water tank] isn’t here. So there’s nothing. Just this little house,” said Gomez.

But her little house could eventually be torn down and reconstructed, according to the institute’s plans for the homes in Santiago el Pinar. But the plans for Santiago el Pinar haven’t been finalized.

A new vision and stability in management may be exactly what the program needs, said Gamboa, who held the top spot at the institute for the first half of 2011. Several people have rotated through as heads of the program since.

“The Rural Cities [program] needs a person in charge that has a real conviction within the program, that knows it, that takes ownership of it and that can generate policies in all of the rural cities. Especially in the economies that will allow people to receive income that they can spend within the rural city and not outside of the it so the money that is generated can stay in the city so that it turns into a city with riches and not debts,” stated Gamboa.

Until then, the Gomez family will continue to live in their deficient housing in an empty city surrounded by unfulfilled promises and broken services. Every day they see the see the assertive statement of the government that pledges action not promises: “Son hechos, no palabras.” It is painted in public spaces, printed on their houses and stamped into the paths they walk. They can only hope that one day the words will turn into action.