U.S. Set to Deploy More Drones Along U.S. Borders, Despite Concerns about Effectiveness and Cost

VIDEO: U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials based at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, on the Gulf Coast of Texas, use unmanned aerial systems or "drones" to remotely patrol the U.S.-Mexico border. Video By Trahern Jones and Alex Lancial.

By Trahern Jones

Cronkite Borderlands Initiative

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas — Despite critical reports saying that the use of drones to patrol the nation’s borders is inefficient and costly, the leading Congressional proposal for immigration reform would drastically expand their use.

In fact, the compromise bill would have U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which currently has a fleet of 10 Predator drones, using the unmanned aircraft to patrol the southern border with Mexico 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

An expanded drone program is also sure to draw the ire of privacy advocates who already worry that increasing use of unmanned aircraft will result in intrusive surveillance of U.S. citizens.

The proposal for around-the-clock drone use flies in the face of recent reports from the Government Accountability Office and the Office of the Inspector General.

In a 2012 report, the OIG estimated that the agency only used its current Predator fleet about 40 percent of time the time it had projected for use of the crafts. The same report criticized CBP for failing “to obtain reimbursement for missions flown on stakeholders’ behalf,” such as U.S. Border Patrol, local law enforcement or emergency organizations, like FEMA.

Criticism of the program also came in 2012 GAO report that said drone program staff frequently had to be relocated from other regions to support Predator operations on the southwestern border. In spite of such measures, the report noted that air support requests were more often left unfulfilled in this high-priority region when compared to lower-priority areas like the Canadian border.

Initiated in 2005 at a cost of nearly $18 million for each of the 10 drones and their support systems, the use of unmanned aircraft is a relatively new tool for the Custom and Border Protection’s Office of Air and Marine.

While agency officials say that the program is useful in border surveillance, Predator aircraft cannot be launched on a 24/7 basis due to weather conditions and safety regulations.

Unmanned aerial vehicles are usually restricted to regions and altitudes where other aircraft do not share the same airspace in order to prevent mid-air collisions. That’s why CBP’s Predator fleet almost always flies at night, further limiting potential operational hours.

During an April visit to the National Air Security Operations Center in Corpus Christi, Texas, which controls Predator flights over the Rio Grande, Cronkite student reporters observed that high winds deterred launches for four days.

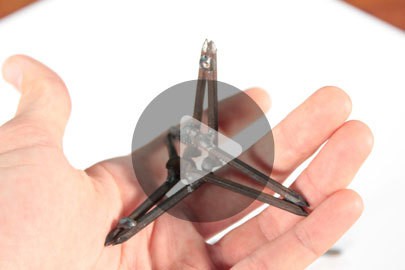

SLIDESHOW: A tire-puncturing device used by drug smugglers to evade Border Patrol agents. Known as "caltrops," such devices are made from steel nails welded together. Photo by Trahern W. Jones |

A pilot for the program, who requested to be unnamed for security reasons, described some of the challenges the agency has had in learning the new systems.

“We’re bringing our people up and getting more experience,” he said. “The technology changes; they can change the software. They can give us new payloads. Things come pretty fast in the unmanned aircraft world as opposed to the manned aviation world.”

The drones fly for an average of seven to nine hours a mission, often covering many miles of uninhabited deserts, rivers and forests. CBP’s Predator aircraft are equipped with high-tech cameras and communications equipment to coordinate with Border Patrol and first responder agencies on the ground. Unlike the Predator program used in overseas military missions, CBP’s fleet does not carry weapons payloads.

The aircraft often provide useful information for agents in complex situations or difficult-to-reach areas, according to Hector Black, border patrol associate Chief, and the agency’s liaison with CBP’s Office of Air and Marine at the Corpus Christi Predator Operations Center.

“When we come across something, we’ll contact the guys on the ground,” Black said in a phone interview. “Rather than sending agents in their vehicle, where it may take an hour and a half or two hours to get out and look at these areas, we can cover it in five or ten minutes with this aircraft.”

The camera equipment aboard CBP Predators is sophisticated enough, according to Black, that even from an altitude of many thousands of feet, “you can actually zoom in and get street names.”

While the same camera equipment can be found on the agency’s manned aircraft, the Predator’s longer flying time allows for increased surveillance and more immediate responsiveness to situations on the ground, according to CBP officials.

In attempting to measure the successes or failures of the program, Black cautioned that metrics like apprehensions, seizures or flight hours might not be appropriate. Predator missions are often used for intelligence-gathering purposes, alongside interceptions of illegal crossings.

A more subtle measure of drones’ effectiveness is how they impact smuggling patterns in areas they patrol, Black said.

“First we’ll see a spike in apprehensions in those zones, and then the spikes will start to show a direct downward trend,” he noted.

Not everyone is convinced of their effectiveness, however. The perceived shortfalls noted by the GAO and OIG represent a systemic problem, according to Ed Herlik, a researcher with Market Info Group, an aviation and defense analysis firm.

“They already don’t fly their Predators much at all,” Herlik said in a phone interview. “We ran the numbers. Part of the time there are no Predators in the air anywhere in the nation and most of the time there might be one.”

“Now, of course they can launch two or three or five if they want to,” he added, “but they almost never do, just by running the averages from what they report from flight times.”

The reason for the program’s existence in the first place may have had more to do with the politics of border security than actual need, according to Herlik.

“The Predators were forced on them” he said.

Herlik explained that such systems were adapted from their wartime purposes in Iraq and Afghanistan for domestic use.

“Congress wanted Predators over the border, therefore it happened,” Herlik said. “The fact that they’re not tremendously useful is not helpful.”

Congressman Henry Cuellar, D-Tex, the co-chair of the House of Representatives Unmanned Systems Caucus, countered that CBP’s drone program is a useful tool to be explored further.

“You need technology, whether it’s cameras, sensors or unmanned aerial vehicles, for example,” Cuellar said in a phone interview. “We need the right mixture of personnel and technology to secure the border.”

Cuellar said the use of technology on the border is “evolving.”

As co-chair of Congress’s Unmanned Systems Caucus, Cuellar came under fire in 2012 when an investigation by Hearst Newspapers and the Center for Responsive Politics revealed that caucus members had received almost $8 million in campaign contributions from unmanned aircraft manufacturers and lobbying groups. Cuellar himself received $10,000 in contributions from General Atomics, the California-based company that produced CBP’s Predator fleet.

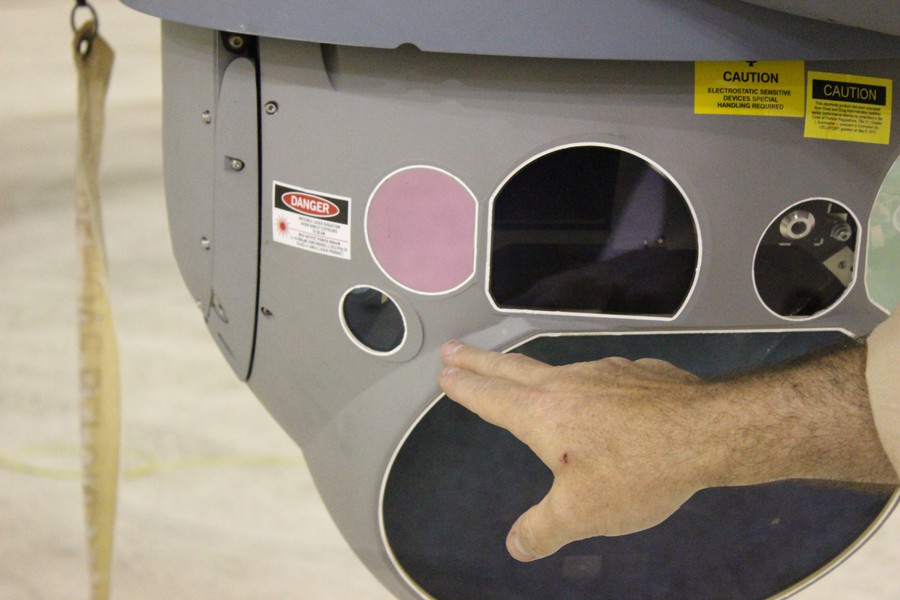

A Customs and Border Protection drone pilot runs through equipment checklists at a ground control station in Corpus Christi, Texas. The agency's fleet of Predator drones are remotely piloted from ground stations like this one. Photo by Trahern W. Jones. |

When questioned about such contributions, he emphasized that, like most members of Congress, he gets donations from a variety of interest groups with conflicting goals.

“I receive campaign contributions from those companies that produce aircraft, that produce technology—in this case, unmanned aerial vehicles—just like I’ve received money from media PACs,” Cuellar said. “They never ask me if their contribution affects me.”

CBP’s Predator fleet has also been criticized for its potential impact on the privacy of U.S. citizens. Amie Stepanovich, a legal counsel for the Electronic Privacy Information Center, said that the use of drones by federal agencies could lead to an overall increase in the surveillance of ordinary citizens.

“They make surveillance cheaper,” Stepanovich said in a phone interview. “So where it costs so many hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars to purchase and operate a helicopter, doing the same thing with a drone is significantly cheaper.”

“The largest, single [civil] drone fleet that we know of is operated by Customs and Border Protection,” she added. “Those licenses are very limited. It took a long time to get them. There was a lot of process involved. They also were not public, so they could be operated without much public accountability or any transparency.”

A problem also arises with the amount of data that CBP’s Predator program collects over time, according to Jennifer Lynch, an attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

“I think one of our biggest concerns is what any of these agencies are doing with their data after they obtain it,” Lynch said in a phone interview. “Storage is so inexpensive that law enforcement and federal agencies could just maintain a library of videos of all the surveillance missions that they’re doing.”

“That’s incredibly problematic because it means the government could go back through that library of information at any time,” she explained. “What we would love to see, is if CBP and other agencies had a policy on deleting the data after a certain period of time.”

At this time, CBP has not described any policy for deleting videos of Predator surveillance footage, although similar policies exist for some law enforcement agencies when collecting photographs of vehicle license plates.

Lynch also said the use of drones will mark an increase in surveillance of U.S. citizens who happen to live in areas patrolled by CBP aircraft.

“There’s a huge percentage of the United States that lives on the border,” Lynch said. “Congress members are proposing legislation that will protect privacy by requiring a warrant for using drones for any law enforcement investigation—but it won’t require a warrant for border search purposes.”

Lynch said the drone program’s impact on regular citizens will be much broader than anticipated.

The use of drones for surveillance of border areas came to a head in North Dakota in June of 2011. In the first known case to involve the use of drones to arrest a U.S. citizen, Rodney Brossart, a farmer from Nelson County, N.D., was apprehended with the aid of a CBP Predator aircraft.

The situation arose after Brossart located several cattle that had wandered from a neighboring farm onto his own. He allegedly refused to return the livestock until the owner paid him for the feed and shelter he had provided during the time he held the cattle. When authorities were called in, the situation reportedly led to an armed standoff.

At one point, a nearby CBP Predator aircraft was alerted to the situation and aided in a local SWAT team’s intervention. Footage from the aircraft constituted evidence in the court case, although it remained confidential, according to Brossart.

“I think it was rather ridiculous,” he said in a phone interview. “You think this was the first time people in the country had their cattle get out of their fence? They wandered off, and they wandered onto another person’s property. The next thing you know, there’s a drone being used.”

“We’re in North Dakota, for Pete’s sake,” Brossart said. “This is very peculiar to me.”

Despite concerns brought up by privacy organizations and the GAO and OIG reports, Customs and Border Protection officials still express pride in the Predator fleet.

According to Tom Salter, the director of CBP’s National Air Security Operations Center in Corpus Christi, the drone program has given agents unprecedented support in halting cross-border drug shipments. He said that almost 22,000 pounds of narcotics were seized last year through the support of the drone program in Texas alone.

“We have good communication with the agents on the ground,” Salter said. “They are thrilled to have us overhead while they are in the brush getting eaten up by mosquitos.”

For Daniel Tirado, a Border Patrol agent on the Texas-Mexico border, these issues can be matters of life and death.

“Agents can get dehydrated and disoriented,” he explained during a ride-along on the Rio Grande. “You get disoriented in the middle of the brush; how can you tell somebody where you’re at and get some help?”

He said the aircraft are at the ready to help agents in danger.

Situations can also quickly arise when smugglers attempt to escape in trucks full of drugs or other contraband, leading to a vehicle pursuit by Border Patrol agents.

“Most of those don’t end up pretty,” Tirado said.

In recent years, smugglers have rammed Border Patrol vehicles or used caltrops—small, spiked clusters of nails that can puncture tires and potentially flip a pursuing vehicle. In such cases, unmanned aircraft can follow the escaping vehicle—for hours, if necessary—and alert agents on the ground.

Still, some industry advocates wonder if Border Patrol agents might be better served by using smaller, hand-launched drones similar to those used by the U.S. Army in overseas operations for short-range surveillance.

Ben Gielow, a government relations manager with the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International, noted border surveillance is a market that manufacturers of smaller drones hope to capture.

“They’ve already proven their worth,” Gielow said in a phone interview. “There’s certainly opportunity at the smaller end of the platform.”

He said “backpack-able, small, unmanned aircraft” were a quickly approaching possibility for Border Patrol agents in the field.

“Oftentimes, agents are going out and responding to a sensor or maybe a report of a sighting, and they’re going out and they’re not really sure what they’re going to come upon,” Gielow said. “Oftentimes, they won’t find out until they get right up on whomever they’re tracking. If you had a small unmanned aerial vehicle that they could deploy using different cameras or sensors, they could determine if those folks are armed. That kind of information could allow them to make better choices that could save lives or protect officers.”

The Department of Homeland of Security has recently opened a Request for Information through the Federal Business Opportunities site, specifically asking for performance specifications for small, unmanned aircraft, such as those that could be hand-launched from the backs of trucks.

The site asks drone manufacturers to “solicit participation in the Robotic Aircraft for Public Safety project from the small unmanned aerial systems (SUAS) for transition to its customers.”

When asked for comment, a spokesman for the Department of Homeland Security’s Science and Technology Directorate stated, “DHS does not intend to expand its use of unmanned aerial systems beyond its current mission scope."

DHS did not confirm or deny if the agency would seek small unmanned aircraft for future use.

For Border Patrol officers on the ground, any aircraft, unmanned or manned, is a critical asset, according to agent Daniel Tirado.

“Any additional resources that we get are always welcome,” Tirado said. “Any equipment that we get is always good. I don’t think an agent will say ‘no’ to any additional tool that you give them. You give them more tools, they’re going to welcome it because it makes the job a lot easier. If you give them bionic vision, they’ll take it.”

Back to Top